2023 Budget Season Recap

Windfalls, Tax Relief, Spending

Rishi Sondhi, Economist | 416-983-8806

Date Published: April 26, 2023

- Category:

- Canada

- Government Finance and Policy

Highlights

- Across governments, robust economic growth drove unexpected revenue windfalls and much better-than-anticipated fiscal performances last year. At $31 billion, the combined federal/provincial FY 2022/23 deficit was about $50 billion less than forecast at the time of last year’s budgets.

- Fiscal positions in the year ahead are set to deteriorate as economic growth slows markedly across the country and policymakers keep spending on priority areas like healthcare, education and inflation relief. A cumulative $4 billion deficit at the provincial level is anticipated for this fiscal year. The federal government, meanwhile, is forecasting a $40 billion shortfall, as Ottawa focuses on an agenda that includes supporting the clean energy transition and providing targeted inflation relief.

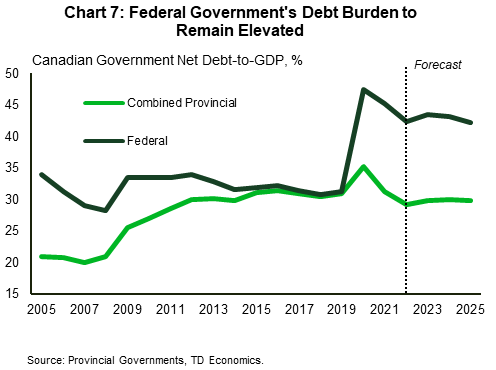

- As a result, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to rise in the year ahead, and to remain significantly above its pre-pandemic level. This suggests potentially less flexiblity for federal policymakers to respond to a worse-than-anticipated downturn.

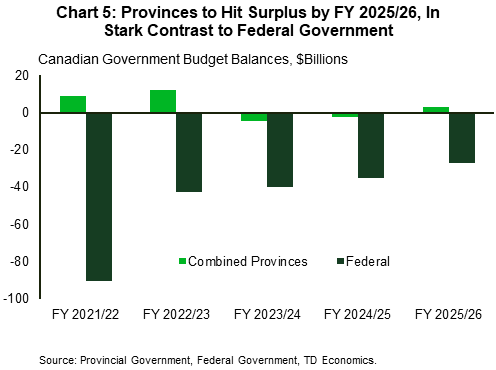

- Provincial budget balances are expected to shift from deficit back to surplus by FY 2025/26, although the all-province net debt burden is expected to edge higher from its current level of 29.1%.

2023 budget season has all but wrapped up, with PEI being the only province left to report, and we’ve teased out several key takeaways. Overall, policymakers are reallocating a share of last year’s unanticipated revenue windfalls to boost spending in priority areas and deliver tax relief while boosting capital investment. However, these measures will come at a cost, with near-term fiscal positions set to worsen in an environment of slowing economic growth.

Much Improved Fiscal Backdrop

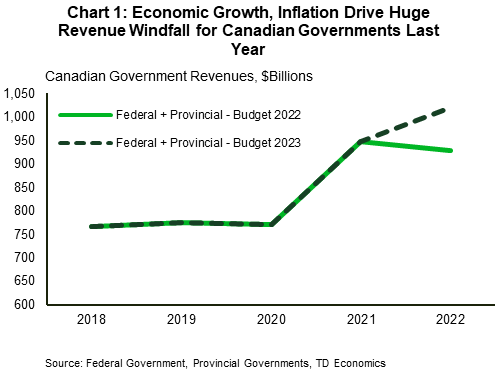

Canadian governments have enjoyed a much better starting point compared to what was expected at the time of last year’s budgets. Nominal economic growth far exceeded budget assumptions in FY 2022-23, driving up federal and provincial revenue some $92 billion higher than anticipated a year ago – amounting to a meaty 3% of Canadian GDP (Chart 1). The largest upside surprises were in Western Canada, where provincial coffers were juiced by surging commodity prices. However, upside surprises were reported across the country.

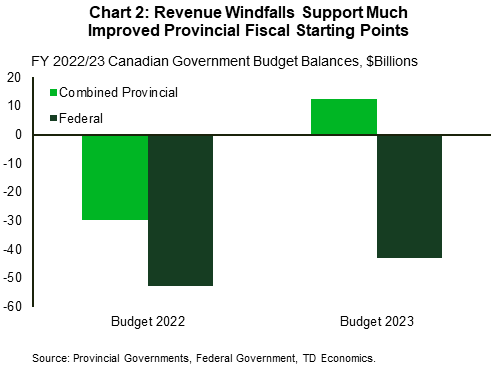

These substantial revenue windfalls contributed to a $52 billion improvement in the combined federal/provincial FY 2022/23 deficit projection compared to estimates laid out in last year’s budgets, as they more-than-offset higher-than-anticipated spending. Now, the FY 2022/23 aggregate provincial/federal deficit is pegged at $31 billion and is entirely accounted for by the federal government. Provincial governments are in much better shape, having run an anticipated $12 billion surplus on the back of improvements in Ontario, B.C., and Alberta (Chart 2).

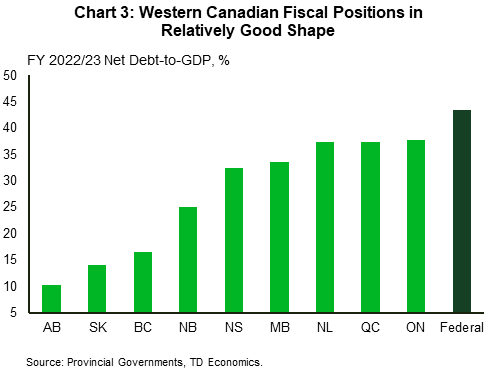

These improved deficit positions and much stronger-than-anticipated GDP growth also lowered government debt burdens compared to last year’s expectations. In aggregate, provinces now peg their FY 2022/23 net debt-to-GDP ratio at 28.9%, versus 32.2% at the time of last year’s budget. Across provinces, those in Western Canada enjoy better fiscal positions than elsewhere in the country (Chart 3). The federal government has also seen some improvement (42.4% now versus 44.9% then), although its debt burden remains well above its pre-pandemic figure.

Fiscal Improvements to be Thrown into Reverse This Year, But Story is Better Thereafter

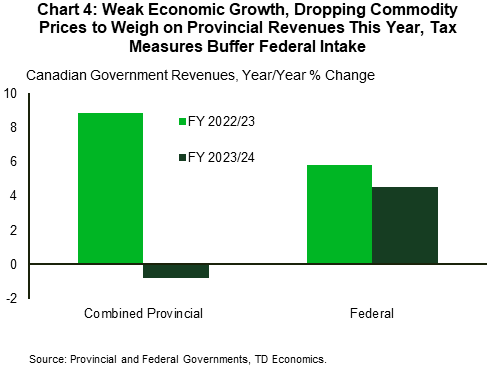

Across provinces, last year’s surprise surplus is forecast to swing to a deficit of about $4.5 billion (0.2% of GDP) in FY 2023/24. This worsening financial position is largely the result of a deteriorating revenue picture, as combined provincial revenues are forecast to drop 1% this fiscal year, despite an 8% gain in federal transfers (Chart 4).

Weighing on this year’s provincial revenue intake is an outlook for slower overall economic growth, a lack of one-off factors that (in some cases) supported revenues in FY 2022/23, lingering housing market weakness and lower commodity prices. Consistent with the latter factor, anticipated revenue declines are steepest in commodity producing provinces, and B.C.

Federal revenues, meanwhile, are more of a curious case, as they’re projected to increase 5% this year, despite forecasted nominal GDP growth (0.9%) well below that figure and the government’s pledge to deliver several investment tax credits in support of the clean energy transition. Part of the story can be put down to new revenue-raising measures (see table 1 for a sample of major revenue measures introduced this budget season). However, the government is also expecting GST revenues to increase at a double-digit pace, which carries some uncertainty given the outlook for softening consumption, and their pledge to deliver $2.5 billion in inflation relief this year through the GST system.

Government revenue projections are subject to downside risks due to an uncertain economic backdrop. However, upside risks are also present. For one, government revenue forecasts for this year were based on commodity price assumptions that could prove too conservative. What’s more, economic growth was more resilient to start the year than forecasters had expected.

After this fiscal year, provincial governments are targeting another razor thin aggregate deficit in FY 2024/25, before moving into small surplus territory by FY 2025/26. Nearly all provinces except B.C., Manitoba and Nova Scotia plan to be in a surplus position by FY 2025/26 and this profile is much better than what was expected at the time of the fall fiscal updates (Chart 5). The federal government, meanwhile, will run shrinking, but continued deficits through their projection horizon.

Spending Growth to Slow, Levels to Remain Elevated

On the heels of a 7% gain in FY 2022/23, combined provincial program spending is set to increase by 2% this year, roughly in line with projected spending at the federal level. There is some variation among provinces with respect to spending, as its above 3% in 4 of 9 provinces reporting so far (led by B.C. at nearly 8%), and below this threshold in the rest.

Notably, healthcare spending takes top billing in several provincial budgets this year, reflecting the rollout of expanded federal healthcare transfers. However, education spending is similarly robust – in part a function of the federal/provincial daycare agreements. In other categories, spending is forecast to pull-back across provinces in FY 2023/24. Federal spending, meanwhile, is concentrated in healthcare transfers to provinces, the green energy transition, and a new dental care plan for low and middle-income households.

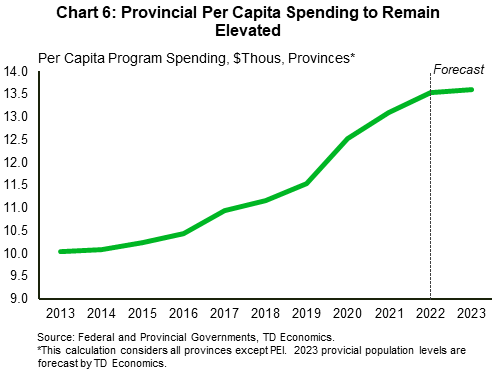

In per capita terms, federal and provincial spending is forecast to be about 20% higher than its pre-pandemic level this year, marking the 4th straight year of elevated expenditures (Chart 6). And, per capita spending is poised to remain elevated over the medium term.

New “Inflation Relief” Funding a Step Down

Relative to prior fiscal updates, we estimate that combined new federal and provincial fiscal measures amount to 0.9% of Canadian GDP this year. This estimate matches what the Bank of Canada outlined in its April Monetary Policy Report and could complicate the central bank’s job of returning inflation to target.

Part of this stimulus is a new set of affordability measures aimed at easing the inflation burden on households. These measures are a mix of tax cuts, rebates, and spending initiatives that, by our reckoning, total about 0.3% of Canadian GDP in 2023. However, this marks a considerable step down from supports implemented previously, notably from Quebec and the federal government. The former jurisdiction went from issuing considerable inflation relief cheques and enhancing seniors assistance to minor reductions in income tax rates for the bottom two brackets. Meanwhile, prior to Budget 2023, the federal government had pledged some $12.1 billion in a suite of affordability measures. Now, their focus has shifted to delivering smaller, targeted relief to low and middle-income-families.

Capital Spending Featured Heavily

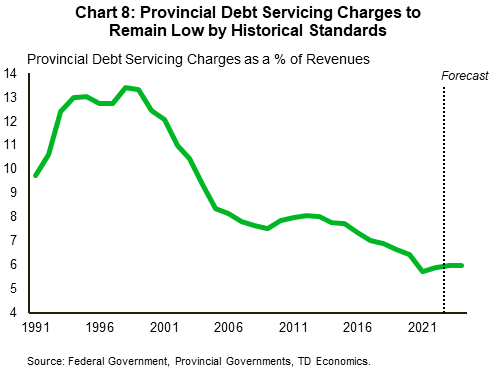

We estimate that provinces plan on boosting capital investment by about 15% in FY 2023/24. This hefty total helps upwardly pressure provincial debt burdens over the medium term. Indeed, in the Big 4 provinces, combined net debt-to-GDP ratios are projected to increase to around 30% this year and remain around that level through FY 2025/26. Still, this level is well below historical peaks (Chart 7). As a result, while debt servicing charges (as a share of revenues) are expected to grind higher, they too are likely to remain relatively low on an historical basis (Chart 8). The federal debt burden, meanwhile, is forecast to remain relatively elevated over the medium term but several rungs down from its peak of 66% in the 1990s.

We should also exercise some caution around capital spending forecasts made in the budgets, given Statcan’s most recent investment intentions survey pointed to a more subdued increase this year.

Bottom Line

Massive upside growth surprises padded government coffers last year, paving the way for near-term spending on priority areas like healthcare, education, inflation-relief, and the clean energy transition. There are also plans to bolster capital spending. Notably, the latter has the potential to enhance longer-term economic growth.

Fiscal positions will worsen in the near-term as economic growth slows. That said, provided that the economy manages to avoid a turbulent landing, Canadian governments appear well positioned to meet their fiscal targets. This year’s round of budgets generally built-in cautious planning assumptions and several provinces continued to build in sizeable contingency reserves. The overall provincial debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to remain below its pre-pandemic level in the coming years even as wide variations persist across jurisdictions. This contrasts with the federal debt burden which is forecast to hang up above its level prevailing before the start of the health crisis – a trend that could potentially reduce its flexibility to respond in the event of a worse-than-anticipated downturn.

Table 1: Selected Budget 2023 Tax Measures

| Jurisdiction | Measure | ||||||||

| MB | Increasing basic personal amount & tax bracket thresholds | ||||||||

| ON | New manufacturing investment tax redit, expanded access to small business rate | ||||||||

| QC | Reductions to income tax rates for bottom two brakets | ||||||||

| NB | Implementing previously announced cuts to personal income tax rates | ||||||||

| NS | Expanding acces to the the MOST tax refund | ||||||||

| Federal | 2% tax on stock buybacks | ||||||||

| Dividends on Canadian equities held by financial institutions taxed at a full rate | |||||||||

| Investment tax credits to stimuluate clean energy investment | |||||||||

| Alternative Mininum Tax (targeted at high income individuals) rate, exemption threshold increas | |||||||||

| Implementing one-time $2.5 billion "Grocery Rebate" | |||||||||

| Reinforcing intentions to implement a Global Mininum Tax on Multinationals of a sufficient size | |||||||||

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: