The Times They Are A-Changin’:

Germany and the E.U.’s Economic Outlook

Andrew Hencic, Senior Economist | 416-944-5307

Date Published: March 27, 2025

- Category:

- Global

- Europe

- Global Economics

Highlights

- Despite uncertainty from trade, the outlook for Germany and the E.U. has been upgraded for 2026 due to the ambitious fiscal agenda out of Berlin.

- We caution against too much exuberance, however. Large-scale public investment takes time, so we remain wary on the outlook, emphasizing that the near-term is likely to remain bumpy, with fiscal flows in late-2025 and into 2026 possibly bringing relief.

- Canadian multinationals have increased exposure to the E.U. in recent years, opening the door for Canadian firms to benefit from the potential upside to growth.

After two years of weak growth, Germany and much of the E.U. looked to be set for another tepid year in 2025. However, Germany’s incoming government looks to be going beyond added defense outlays and funding much-needed infrastructure investment. Our new outlook incorporates the increased German public investment spending linked to the new infrastructure fund. Moreover, given concerns about Russian aggression, a political shift has occurred in the E.U. towards relaxing fiscal rules to fund a large continental rearmament. The E.U. and German strategies for rearmament have yet to be fully refined, so we have yet to incorporate them into the outlook, only noting that there is still room for greater upgrades to growth, inflation, and interest rates in the coming quarters.

The Baseline

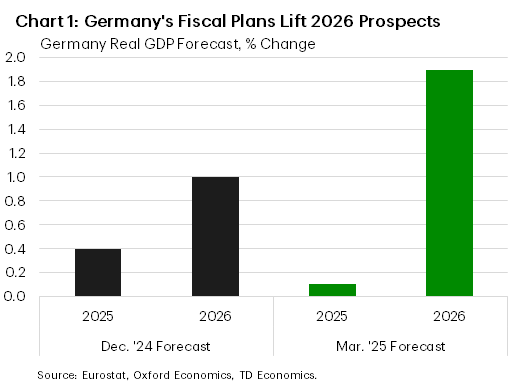

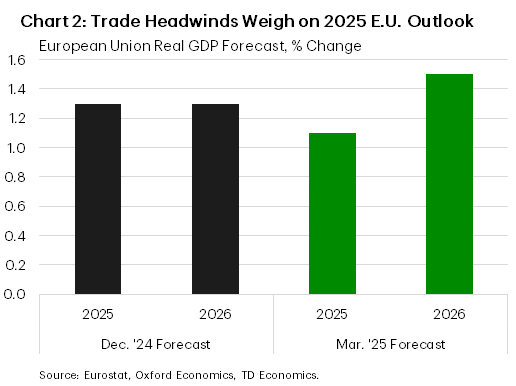

Our updated projections are underpinned by our assumptions about the course of global tariffs. We assume tariffs rise to a level not seen in decades through the third quarter of 2025, before gradually beginning to fall. As tariffs increase, so does economic unease, and the two factors conspire to weigh on growth. As such, we have downgraded GDP growth in Germany, the euro area, and the E.U., to 0.1%, 0.7%, and 1.1% year-on-year (y/y), respectively, in 2025 (Chart 1 and 2).

Our baseline does not yet incorporate the potentially substantial expenditures as part of the ReArm Europe initiative. Current proposals involve a sizeable 150 billion euros in common borrowing, amounting to 0.8% of 2024 E.U. GDP. In addition, the activation of a fiscal escape clause (allowing governments temporary exemptions from bloc-wide deficit limits) has been proposed that would open an additional 650 billion euros (3.6% of 2024 GDP) over four years to lift defense spending by 1.5% of GDP1. Since we don’t yet know the details on the possible structure and coordination of the outlays, we have omitted them from the forecast.

In contrast, growth in Germany has been upgraded markedly in 2026. The Bundestag has voted to approve a constitutional reform that would omit defense spending above 1% of GDP from the government’s official deficit. This was the first major hurdle, and now states need to ratify the agreement. In addition, a large public investment fund is to be established to address the country’s substantial infrastructure needs (something we highlighted in our report last fall). The scale of the public investment initiative, however, is far beyond what we had envisaged.

The approved framework2 is for a 500 billion euro fund (11.4% of Germany’s 2024 GDP) to be disbursed over the course of 12 years (roughly 0.95% of GDP per year). Of those funds, 10% will be allotted to already budgeted investments with the remaining 90% devoted to new initiatives. The money will be divided between federal spending (300 billion euros), climate investments (100 billion euros) and transfers to state governments (100 billion euros). It also opens the door to state borrowing, though that requires further legislative action at the state level that is uncertain and not included in our forecast.

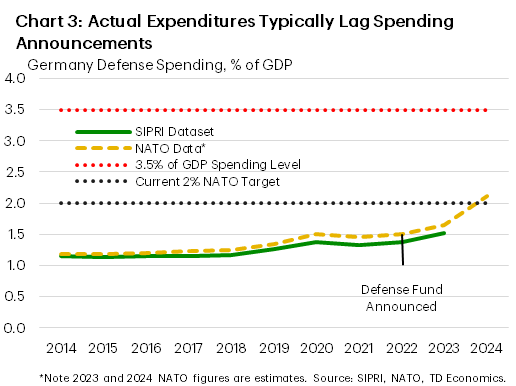

Although the scale of the fund is large, we tempered our expectation for the pace of disbursement and considered possible offsets, limiting the upside to the outlook. First, even after the fund is set up, it can take time for money to be spent. For instance, when the defense spending fund was first announced in 2022, defense spending rose by roughly 5.8 billion euros in 2022, 9.3 billion euros in 2023 and estimated 22.9 billion in 2024 – taking it over 2% of GDP (Chart 3). Secondly, despite money being allocated, a known issue facing Germany has been money not actually being spent due to administrative hurdles and a lack of adequate labour3. Thus, we assume spending gradually starts in late-2025, with a ramp-up thereafter.

Another reason for caution is that fiscal restraint in other areas could be seen in the ensuing years. Chancellor Merz has already hinted that some form of fiscal offsets could be coming amid the prospect of substantially increased defense spending and borrowing for public investment. To sustain permanently increased defense spending without ballooning debt, it is likely that there will be some restraint in other areas. The same is likely true in the rest of the E.U., where demands on social spending are high and many governments don’t have much fiscal maneuverability to sustain permanently higher defense outlays.

Therefore, the typical knock-on effects to the broader economy are likely to be less than would be typically expected from these types of outlays. Economists estimate the typical fiscal “multipliers“ (the added lift to the economy government spending provides) in the E.U. at roughly 1.14, but in our forecast the lift to 2026 GDP growth is milder, and Germany’s GDP growth rises to 1.9% for the year. The improved outlook for Germany in 2026 helps improve the overall picture for the E.U., and growth is expected to pick up to 1.3% for the year.

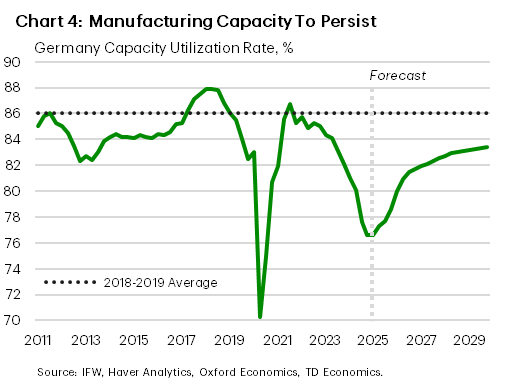

The forecast for inflation is sensitive to both the negative macroeconomic outlook in 2025 and uncertain inflationary impact from tariffs. From Germany’s perspective, the excess capacity that has developed in the manufacturing sector is gradually absorbed, albeit not recovering to 2018-2019 levels (Chart 4). This keeps inflation relatively in check through the forecast horizon – the absence of the stimulus would have presented further downside risk. Tariffs on U.S. goods could provide a lift to price pressures, but this could be offset by a greater flow of goods from other countries diverted to the bloc amid increased U.S. trade barriers.

What If Defense Spending Ramps Up Quickly?

Our relatively conservative outlook for public outlays leaves room for upside surprise. If NATO members eventually increasing defense expenditures to 3% of GDP (and possibly more), with a 2.5% intermediate target, as is being rumored, it could notably increase medium-term growth. These are ambitious targets. Italy5 has already expressed concerns about lifting government defense expenditures further. Increases of this scale would likely require substantial uptake of the proposed temporary exemptions from E.U. deficit rules. Given that only roughly 37% of the loans allocated to the Recovery and Resilience fund launched to help the post-pandemic recovery have been disbursed, it suggests that the appetite for substantially increased borrowing among heavily indebted countries remains weak.

Nonetheless, higher military expenditures seem to be a good bet. Increased common borrowing, if spread over 4 years could add roughly 0.2% of GDP per year (if money is spent domestically), which would likely be challenging given known military capability gaps. How these funds are disbursed is also critical. Recent proposals would have roughly two thirds of the money allocated to E.U. companies and the rest to nations that have signed security agreements with the bloc6. Assuming a gradual ramp up that lifts defense of spending among NATO members by 0.2% of GDP, allocating 30% to investment (NATO targets are for 20%), provides a comparable lift to growth across the bloc in 2026. The corresponding upside to inflation is modest, having a peak effect of 0.1% on year-on-year CPI inflation. As an upside scenario, assuming a ramp-up that adds 0.5% of GDP over a year (again spent domestically) would provide a fillip to growth of 0.6%, and 0.2% to CPI. In the latter scenario, some of the additional benefit from the spending could be offset by the ECB having to lift interest rates to contain inflationary pressures.

It is important to note that defense expenditures are likely to provide a temporary lift. The point of the borrowing is to scale-up capabilities in the short-term. Sustaining a higher level of spending over the longer-term is not likely without either increased revenues (i.e. tax increases) or spending cuts to other areas given the E.U.’s fiscal restraints.

Higher taxes or non-defense spending cuts would offset the growth lift from the fiscal expansion, but revenues could also be lifted by stronger trend growth. On the growth side, recent estimates7 of the longer-term productivity lift from increased domestic investment in equipment and tech products suggest that spending on these items could provide positive productivity spillovers of a quarter of the expenditure. Under our spending assumptions above this would represent a modest amount – possibly just under 0.1% per year, at a maximum. While this is likely an upper bound of the productivity benefits, increased defense research and development has also been found to help crowd-in private sector investment8, providing some (albeit limited) boost to higher trend growth.

Canada Could Play a Role

For Canadian firms, there are two interesting avenues of collaboration. First, there is a possibility for Canada to participate in Europe’s ReArm plan. As currently outlined, only countries with security partnerships with the E.U. are eligible for the joint procurement mechanism that is part of the €150 billion joint borrowing initiative. Just over a third of these funds are being allocated to countries that are not part of the E.U. but have defense partnerships with the Union. Canada does not yet have such an agreement but, it has been noted that a Canada-E.U. defense partnership could be set up relatively “quickly”9, possibly making it eligible to participate.

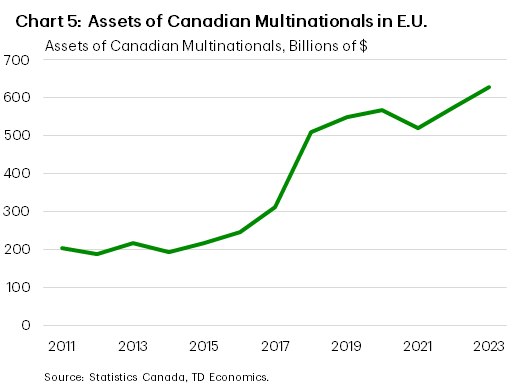

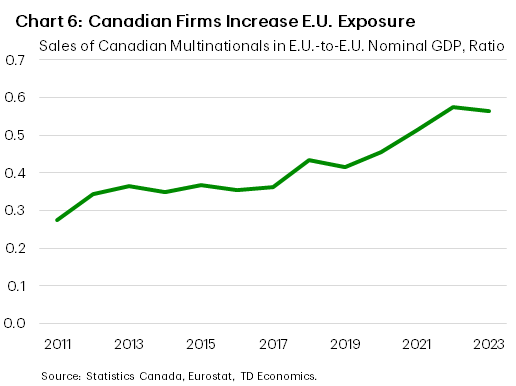

Second, while goods trade may be facing growing protectionism and infrastructure limitations, it only forms part of Canada’s economic relationship with the E.U. Canadian multinationals hold roughly $680 billion in assets in E.U. countries, generating $141 billion in sales in 2023 (Chart 5). In fact, assets of Canadian multinationals have grown an average of 18.7% per year between 2018 and 2023, compared to a tepid 4.2% per year between 2013 and 2018. Importantly, this appears to reflect greater integration rather than simply rising asset prices as the ratio of multinational sales-to-GDP has risen from 0.27% in 2011 to 0.54% in 2023 (Chart 6). This helps open the door for Canadian firms to benefit from the potential upside to growth.

Despite looming trade uncertainty, there are reasons for optimism in Europe. The prospect of a significant infusion of German public investment ushering in a new era of productivity growth is real. However, we caution against too much exuberance. Large-scale public investment takes time, even if there is a sense of urgency among some major economies regarding defense outlays. For the time being, we remain wary, emphasizing that the near-term outlook is likely to remain bumpy, with fiscal flows in late-2025 and into 2026 possibly bringing relief.

End Notes

- European Commission (Mar. 3, 2025) Press Statement by President von der Leyen on the Defense Package https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/sv/statement_25_673; Strupczewski, J. (Mar. 11, 2025) “EU Ministers Back Proposal of Temporary Exemption on Defence Spending in EU rules” Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-ministers-explore-ways-spend-defence-without-breaking-eu-rules-2025-03-11/

- Delfs, A., M. Nienaber, K. Kowalcze (Mar. 18, 2025) “Germany’s Landmark Spending Spree Wins Parliamentary Backing” Bloomberg News https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-18/german-lawmakers-pass-landmark-spending-package-ending-era-of-budget-austerity?srnd=homepage-canada

- European Commission (April 2024), “In-Depth Review 2024 – Germany” Institutional Paper 280

- European Commission. (2024a). Debt Sustainability Monitor 2023. Institutional Paper, 271; Carnot, N., & de Castro, F. (2015). The discretionary fiscal effort: an assessment of fiscal policy and its output effect. European Economy – Economic Papers, 543

- Migliaccio, A., D.P. Mancini, S. Sirletti (Mar. 11, 2025) “Italy’s Bond Agnst Shapes Meloni Strategy From Defense to Banks” Bloomberg News, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-11/italy-s-bond-angst-shapes-meloni-strategy-from-defense-to-banks

- Foy, H., L. Fisher, (Mar. 19, 2025) “EU to exclude US, UK and Turkey from €150bn rearmament fund” Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/eb9e0ddc-8606-46f5-8758-a1b8beae14f1

- Ilzetzki, E., (Feb. 2025) “Guns and Growth: The Economic Consequences of Defense Buildups” Kiel Institute for the World Economy, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/guns-and-growth-the-economic-consequences-of-defense-buildups-33747/

- Enrico Moretti, Claudia Steinwender, John Van Reenen; The Intellectual Spoils of War? Defense R&D, Productivity, and International Spillovers. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2025; 107 (1): 14–27. https://direct.mit.edu/rest/article/107/1/14/114751/The-Intellectual-Spoils-of-War-Defense-R-amp-D

- Mancini, D.P., A. Palasciano, T. Seal T, B. Platt (Mar. 19, 2025) “Canada Seeks Defense Ties and Deals With Europe as US Pulls Back” Bloomberg News, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-19/canada-seeks-defense-ties-and-deals-with-europe-as-us-pulls-back

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: