From Laggard, to Leader, and

Back Again: Germany’s Malaise

Andrew Hencic, Senior Economist | 416-944-5307

Date Published: September 25, 2024

- Category:

- Global

- Europe

- Global Economics

Highlights

- Germany’s economic growth has underperformed the broader euro area for its longest stretch since the collapse of communism in eastern Europe led to German reunification.

- The current malaise is also the result of a supply shock but different from the last period of underperformance. It is expected to be less lasting too, and fade in 2025.

- Beyond that, Germany still faces a shrinking workforce, and rising old age dependency. The need for greater public investment represents an area where incremental improvements could materially lift the outlook.

Germany looks set to underperform the euro area for a fourth year in a row in 2024. This is the longest stretch of underperformance since the late 1990s and early 2000s when the Economist famously labelled Germany, “The Sick Man of the euro”1. The comparisons to this period are overdone. As then, there are serious challenges facing the economy, but while the situation 20 years ago reflected the aftereffects of reintegrating East Germany, the current malaise is the result of the inflation shock stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As inflation continues to fade, Germany’s growth should gradually return heading into next year, helping the economy expand 1.0% in 2025. However, challenging structural issues, including demographic headwinds and inadequate public investment, loom on the horizon and will need to be addressed in the coming years.

History is Not Repeating

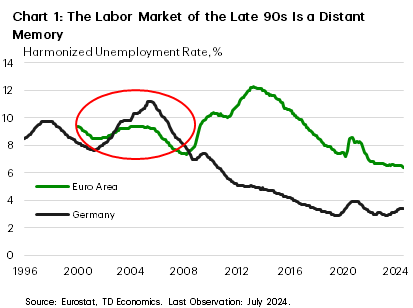

When Germany’s economy underperformed in the late nineties, it was in the wake of the reunification of East and West Germany. The associated costs of infrastructure and capital upgrades, fiscal transfers and social expenditures were massive. Total transfers to the former East Germany are estimated to have been over 1 trillion euros from 1991 to the early 2000s alone, a sizeable 3-5% of total German GDP in each year2,3. Moreover, the structural change imposed suddenly on East Germany’s communist economy saw the unemployment rate rise into double digits by the early 2000s (Chart 1). Chancellor Gerhard Schroder’s governing coalition undertook the Project 2010 initiative in response, in hopes of kick-starting growth and bringing down unemployment. The Hartz Reforms restructured labor arrangements and, in 2005, reduced long-term unemployment benefits. In the years that followed, the unemployment rate continued to fall, albeit raising the earnings penalty to being unemployed4,5. Nonetheless, the German unemployment rate (adjusted to reflect euro zone measurement) now sits at a low 3.4%, far below the average across the euro area and its own historic highs.

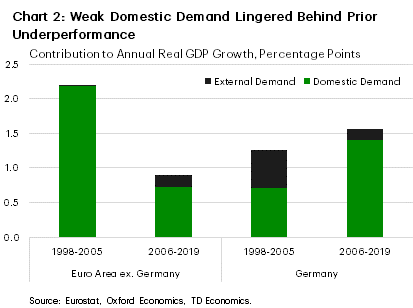

Given that the last of the reforms were implemented in 2005, this is a convenient cut-off point in the data to examine the drivers of German economic growth relative to the rest of the euro area. Between 1998 and 2005, given the high rate of unemployment, Germany’s economy relied heavily on external demand. In that time, roughly half of GDP growth was attributable to an improving trade balance. Conversely, the rest of the euro area expanded at a solid clip, virtually entirely supported by domestic demand (Chart 2).

Between 2006 and 2019 the euro area sovereign debt crisis damaged the eurozone economies, while Germany became an economic standout. Healthy domestic demand and a positive contribution from trade were the envy of Europe prior to the pandemic. However, these were upended by COVID lockdowns and the gargantuan spike in energy prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Germany relied on Russia for over half of its natural gas supplies, and the steep run-up in energy prices led to a fall in consumer (and investor) confidence, which has depressed domestic demand.

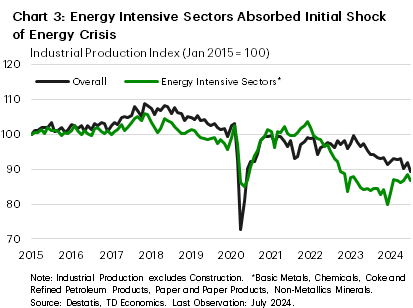

The silver lining is that the economy has weathered the shutdown in Russian gas imports better than many had feared. Although the energy shock profoundly affected energy-intensive industries (Chart 3), the steep reduction in energy demand, along with substitution to alternate suppliers (mostly LNG from the U.S.) helped the country avoid a steep economic contraction6.

Fading Shocks Lift Prospects

The good news is that the worst of the shock is likely in the rearview mirror. Demand growth is expected to begin to recover in the latter half of 2024 as wages in inflation-adjusted terms continue to rise. Improving domestic economic prospects have gradually been translating into a bump in consumer confidence, as the decline in living standards abates.

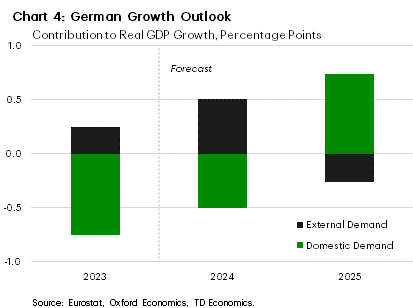

A revival in real wage growth (+3.0% y/y in Q2), combined with falling interest rates should help private consumption return to the driver’s seat and power growth in 2025 (Chart 4). The associated jump in consumer demand will be partially offset by rising imports, with a still lackluster global growth backdrop not providing much of a fillip to export orders.

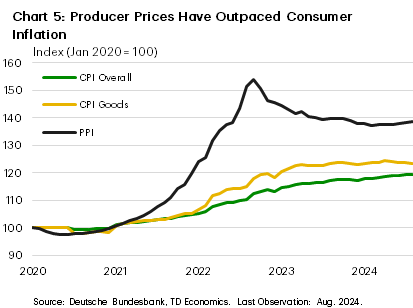

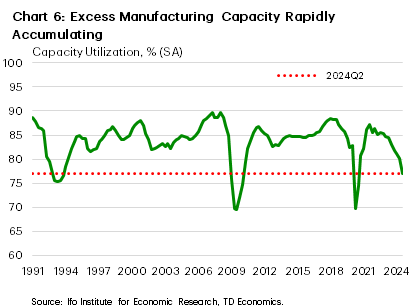

However, the investment landscape is likely to remain challenging. Business sentiment remains moribund. Corporate sector cost structures have shifted materially in the past four years, with the restructuring of the energy market, and sharply higher input costs are eating into margins (Chart 5). Moreover, the erosion in real incomes had suppressed pricing power, limiting firms’ ability to support margins by raising prices. This will weigh on investment prospects. Segments of industry are reportedly suffering from overcapacity (Chart 6), with Volkswagen’s high-profile discussions about shutting factories emblematic of the current state of industry7.

Nonetheless, the bottom is due. Interest rates are at multi-decade highs and are expected to continue falling as the ECB eases monetary policy, which will help reduce financing costs. Moreover, the rundown in inventories that has acted as a drag is expected to abate heading into 2025. This sets the stage for rising real incomes to help support demand growth. Together, the investment outlook should brighten and begin to gradually recover in 2025.

While the private sector is expected to find its footing, government will be slowly withdrawing its support for the economy. The general government deficit is expected to slowly shrink over the next two years as the fiscal rules that were suspended during the pandemic come into effect.

Opportunities for Long-Term Prosperity

The economy is forecast to resume growth in 2025 after roughly two years of stagnation. This will come as the effects of shocks fade. However, like in the early 2000s, to achieve sustained growth in living standards, policymakers must turn to address the challenges facing the long-run growth. Typically, long-run growth boils down to, how many people (and hours) are available for work, how much they have to work with (capital), and how effectively these inputs are used (productivity). Germany needs progress on all three fronts.

The latter is an area of great study, with former ECB head Mario Draghi recently delivering a comprehensive list of policy proposals8 to boost competitiveness in the European Union. For Germany specifically, a shrinking working age population and slow capital accumulation are pressing concerns that can be readily addressed.

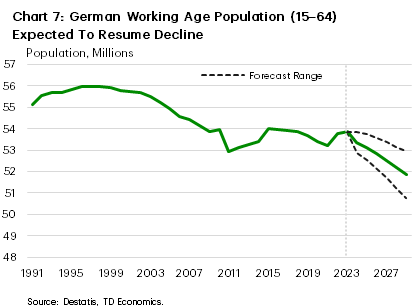

First, the working age population is set to resume shrinking after two major influxes of immigration helped stem demographic declines (Chart 7). The European Commission has already estimated the impacts on government budgets and GDP9. The total drag on potential growth from the shrinking share of the working age population is estimated to be 0.2 percentage points (with some offset coming from higher participation) and the added strain on government coffers projected at 1.5% of GDP by 2045. This is doubly worrying as older workforces have also been associated with declining productivity growth10, making the added productivity lift needed for rising living standards harder to come by.

The textbook answer to the challenges would be to boost investment and participation rates. On the latter front, female labor force participation is still roughly eight percentage points below that of men. Inducing a greater share of women into the workforce could help stem the tide of aging. A feat that is easier said than done given the complex tax and cultural factors that influence labor participation11,12.

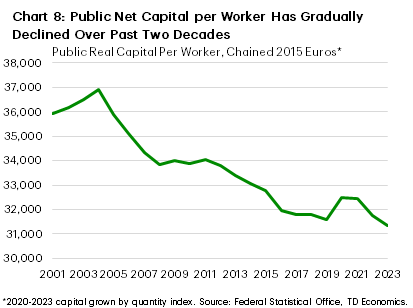

Boosting capital available also comes with challenges but, in Germany’s case, public investment is an area of opportunity. Net public capital per worker has been in a steady decline over the past two decades (Chart 8), while general government debt-to-GDP, after peaking around 87% of GDP in 2012, has fallen to below 62%. The situation has been highlighted elsewhere, but the implications of the problem were neatly summarized in the European Commission’s annual report this year13 that cited survey data suggesting that “the declining quality of public infrastructure and the insufficient modernization of public services are hindering business activities”14.

There are a variety of factors behind the lack of spending. To a certain extent the current fiscal rules, enshrined in the Basic Law, limit the scale of deficit spending outside of emergencies. However, even amid budgetary surpluses, allocated funds had not been dispersed at the municipal level, as a complex permitting environment and lack of labor impeded spending15.

The good news is that on the permitting front, some progress is being made. Recent data suggest a healthy uptick in the number of wind and solar projects allowed to proceed16 after policymakers identified it as a priority area. There are still hurdles to getting the projects online, but the improvement is emblematic of the types of initiatives needed to get investment flowing.

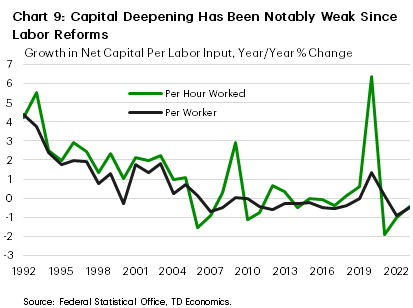

This investment will be crucial to meet climate goals17, deepen the capital stock, and facilitate productivity growth. Moreover, the risk that a glut of capital would be poorly allocated is likely small, given that total capital per worker (public and private) has barely risen in the past twenty years and businesses have articulated a need for infrastructure improvements (Chart 9).

This all ultimately leads back to Germany’s ongoing large trade surplus. Without getting into too deep an economics lesson, Germany’s current account surplus means that it has excess savings as a country – it’s rate of investment is lower than domestic savings (public and private). Despite the need for more capital at home, Germany continues to be a lender to the world. The expected revival in consumption expenditures and investment in 2025 will work to eat into the trade balance, but more can be done. Increased public investments could help facilitate the next era of productivity growth, thereby helping grow living standards at a time when the working age population again resumes its gradual decline.

Bottom Line

German reunification ultimately resulted in large reforms to the labor market that contributed to the decade of resilient economic performance, despite widespread weakness elsewhere in the euro area. Today, policymakers are faced with a new set of challenges coming out of the energy crisis. Despite the headwinds, there is still an opportunity to set the economy up for the next decade of prosperity. Greater public investment represents an area where incremental improvements could materially lift the outlook and help address Germany’s productivity challenge.

End Notes

- The Economist (Jun. 1999) “The Sick Man of the Euro” https://www.economist.com/special/1999/06/03/the-sick-man-of-the-euro

- Burda, M., J. Hunt (2001) “From Reunification to Economic Integration: Productivity and the Labor Market in Eastern Germany” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2:2001

- Jansen, H., (2004) “Transfer to Germany’s Eastern Lander: A Necessary Price for Convergence or a Permanent Drag?” ECFIN Country Focus. Economic Analysis from the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Volume 1, Issue 16.

- Woodcock, S.D., (2023) “The Determinants of Displaced Workers’ Wages: Sorting, Matching, Selection and the Hartz Reforms” Journal of Econometrics, 233(2): 568-595

- Engbom, N., E. Detragiache, F. Raei, (2015) “The German Labor Market Reforms and Post-Unemployment Earnings” IMF Working Paper, 15(162): 1

- Moll, B., M. Schularick, G. Zachmann (Sep. 27, 2023) “The Power of Substitution: The Great German Gas Debate in Retrospect” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall. 395-455

- Raymunt, M., C. Rauwald, (Sep. 2, 2024) “VW Weighs First-Ever Germany Plant Closures to Cut Costs” Bloomberg News: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-09-02/vw-plans-to-close-plants-in-germany-after-cost-cuts-fail-to-deliver

- Draghi, M., (Sep. 9, 2024) “The Future of European Competitiveness” https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en

- Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (Apr. 18, 2024) “2024 Ageing Report” European Commission Institutional Paper 279: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/2024-ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary-projections-eu-member-states-2022-2070_en

- Maestas, N., K.J. Mullen, D. Powell (April 2023) “The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force, and Productivity” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 15 (2): pp 306-32

- Martinez, M. (July 31, 2024) “Germany Leaves Women’s Labour Power Untapped” Reuters News: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germany-leaves-womens-labour-power-untapped-2024-07-31/

- Jessen, J., S. Schmitz, F. Weinhardt (2023) “Immigration, Female Labour Supply and Local Cultural Norms” The Economic Journal, Volume 134, Issue 659, April 2024, pp 1146-1172

- European Commission (April 2024), “In-Depth Review 2024 – Germany” Institutional Paper 280

- Puls, Thomas / Schmitz, Edgar (2022): Wie stark beeinflussen Infrastrukturprobleme die Unternehmen in Deutschland?, IW-Trends, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft.

- European Commission (April 2024), “In-Depth Review 2024 – Germany” Institutional Paper 280

- Martin, M., A. Rathi (Aug 27, 2024) “The Secret Behind Germany’s Record Renewables Buildout” Bloomberg News https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-08-27/how-germany-sped-up-its-deployment-of-solar-and-wind

- Reuters (Oct. 2021) “Germany Needs to Invest $1 Trillion to Hit Climate Target” https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/germany-needs-invest-1-trillion-hit-climate-target-2021-10-21/

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: