Global Supply Chains:

Two Steps Forward and One Step Back

Andrew Hencic, Senior Economist

Date Published: March 28, 2022

- Category:

- Global

- Global Economics

Highlights

- Supply disruptions have been a key contributor to the multi-decade high in inflation in the U.S., Canada, and many other major economies.

- After a period of modest improvement, the war in Ukraine and rising COVID cases in China now present new challenges for producers to navigate.

- Beyond the well publicized bottlenecks, a key contributor to the supply chain troubles has been the unprecedented rise in demand for goods. Waning demand in the latter half of 2022 will help bring relief to producers.

- A high degree of uncertainty about the outlook persists as the pandemic and geopolitical risks dominate the economic landscape.

One of the hallmarks of the pandemic economy has been the supply chain disruptions that have slowed the economic recovery and contributed to multi-decade high inflation in the U.S., Canada and many other major economies around the world. After a few months showing tentative signs of improvement, global supply chains have been upended once again by the conflict in Ukraine. But that hasn’t been the only recent setback. A resurgence of COVID cases in China has caused shutdowns in major economic hubs, which are likely to have at least some ripple-effect to global production systems in the weeks ahead.

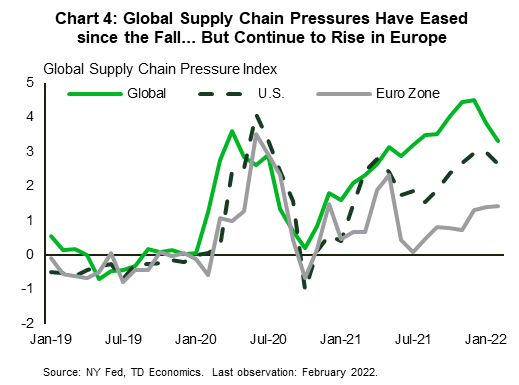

Given the fluidity of the Ukraine situation in particular, it remains too early to assess to the extent that supply chains may be set back in the months ahead. Our hunch is that while certain industries are facing more outsized near-term challenges – notably food, energy and automotive – we doubt that overall disruption measures will deteriorate back to the extremes seen last summer. Indicators released so far in March are consistent with this storyline, with the most profound effects being felt in Europe.

At the same time, however, much will depend on how the demand side of the equation evolves in the coming months. As long as U.S. goods demand remains in the stratosphere, sustained improvement in global supply chains will remain elusive and leave them vulnerable to further snarls.

Exorbitant Demand has Been a Key Culprit Behind Current Vulnerabilities

Since becoming a top economic headline over the past two years, supply-chain issues have been somewhat mischaracterized. Challenges in getting goods out of factory gates through to the end consumer have been complicated by a virtual “whack-a-mole” of developments, many of which have been one time in nature. Still, persistent elevated demand for goods during the pandemic has been arguably the more important culprit in recent quarters.

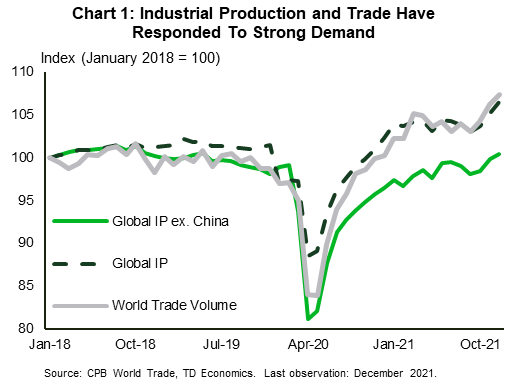

As Chart 1 shows, global industrial production and trade continue to hover at record highs, fully recovering from the initial pandemic shock in 2020 (Chart 1). China’s presence here has been profoundly felt, as it has been the principal driver of industrial growth out of the pandemic. Producers have done an admirable job in growing output and exports under the circumstances but have simply been unable to keep up with the astronomical increase in demand for goods.

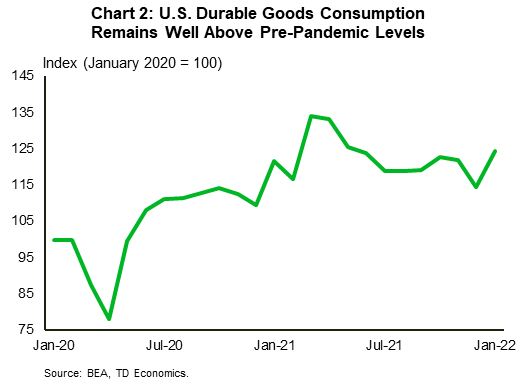

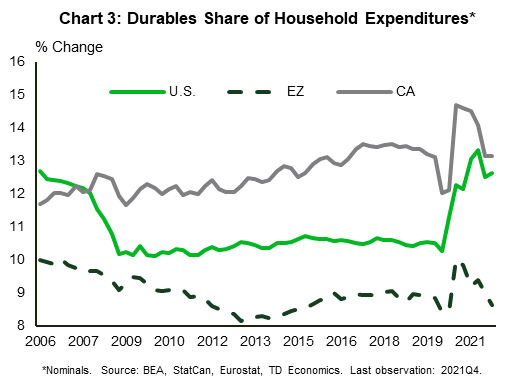

As noted, much of the current challenge reflects circumstances in the world’s largest consumer – the United States. Having benefitted from extraordinarily favorable credit conditions, large fiscal stimulus packages, and substantial wealth gains consumers spent heavily on durable goods (Chart 2). This demand has started to level off but remains a hefty 24.3 percent above its pre-pandemic level as of January, whereas services spending has followed a more gradual path – slowly recovering to its pre-pandemic level. Moreover, a large share of goods purchases has been on big ticket items, which tend to involve the most complex supply chains and intermediation. In contrast, Canada, the U.K., and the Eurozone have recorded strong recoveries in goods demand, but to levels more in line with pre-pandemic conditions (Chart 3).

With markets functioning, the growing shortages have manifested in price signals. Goods price inflation in the U.S. has exceeded that of other major economies. February saw goods inflation run at a double-digit pace – nearly eight percentage points higher than that of services inflation. However, given the strains on global capacity is has also driven goods prices higher in Canada (+7.6%), the U.K. (+8.3%) and the Eurozone (+8.3%) – twice, or more, the respective rates of services inflation.

Fall and Early Winter Brought Some Relief

Based on data released in late 2021 and through the turn of this year, it looked as though the worst of the supply-demand mismatch may have been behind us. The NY Fed tracker (an amalgam of multiple supply side indicators) suggested that strains may have peaked in October (Chart 4). Some signs of improvement included:

- Some softening in goods demand through the autumn that was likely fueled by early buying ahead of the holidays and Chinese New Year. This slowdown, combined with increased operating hours, helped to clear container backlogs in key ports, including the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Although images of ships waiting at anchor were emblematic of the transportation problems, they are hardly a comprehensive economic indicator. So, the pause in freight rate inflation (having fallen since September) and improved readings on supplier delivery time PMI measures have confirmed that this has indeed been a broader trend.

- As supply chains conditions have improved, businesses have managed to restock some inventories. In the U.S. and Canada, inventory build-up contributed 4.9 and 0.7 percentage points, respectively to growth in the fourth quarter of last year.

- Even as Omicron bore down on North America and Europe to start 2022 – causing increased absenteeism and lockdowns – supply chains appeared to make further gradual progress - even withstanding temporary blockages at the Canada-U.S. border. In the U.S., the ISM manufacturing survey showed manufacturing inventories have continued to grow. Moreover, the customer inventories subindex reflects fewer customers reporting inventories are too low.

However, just as things were looking up, the surge in Omicron cases and the war in Ukraine have again put a dent in supply chains.

War in Ukraine is a Major Setback

The outbreak of war in Ukraine in late-February has dealt another blow to global supply chains largely through disruptions to the flow of raw inputs. Beyond the slew of government sanctions imposed on Russia, firms have been reportedly enacting voluntary measures to limit the purchase of Russian commodities. Supply concerns have been accentuated by destruction to Ukraine’s commodity-producing infrastructure. Ukraine is also a top producer of grains and neon gas, with the latter being a key input into the production of global semi-conductors.

Among the major economies, European producers have stronger direct trade linkages with Russia and Ukraine and thus face relatively more exposure. It didn’t take long for German auto manufacturers to announce plant shutdowns due to a shortage of harnesses for wiring – a stark reminder of the fragility and opacity of lean supply chains. Although Ukraine only represents less than 0.01% of European vehicle and auto parts imports, the elimination of the source of a bespoke key component led to major disruptions in automotive production.

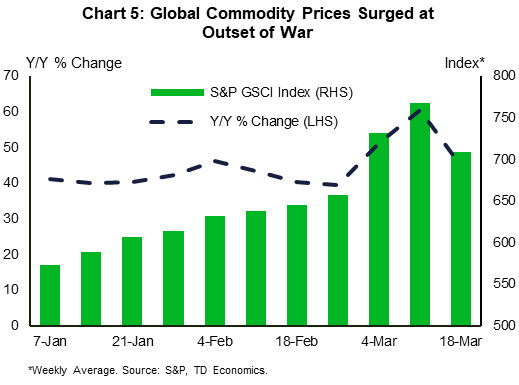

For North America, the knock-on effects to broader global commodity markets will still leave buyers scrambling for new sources of supply and facing sharply higher input costs. The shock couldn’t have hit at a worse time for commodity markets given unusually low stockpiles – particularly of wheat, crude and nickel. Prices for these commodities are up 71.9%, 56.2%, and 174.0% year-over-year, respectively, helping lift broader commodity prices 46.7% higher this year (Chart 5).

In addition to food producers, the auto and electronics sectors are among the most exposed as the disruption to neon gas supplies has further clouded the recovery timetable around semi-conductors – despite Taiwan’s Economic Ministry offering reassurance of sufficient supplies in the near term. For the auto sector, this further shock is a particularly disappointing development given the recent signs of improvement in both sales and production. Another round of downward revisions to production targets seems inevitable, further hampering sales.

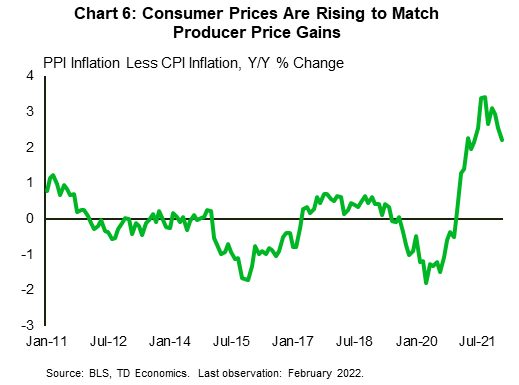

More broadly, rising prices of energy and other raw inputs will be passed on to finished goods. In more regular circumstances manufacturer margins would be able to adjust and absorb fluctuations in operating costs to offset the impacts to final consumers. However, we are now roughly one year into a historic global supply shock and producers have already started passing costs on to end consumers. The added leg higher in input costs is sure to continue adding pressure to final sales prices (Chart 6).

Mercifully, at the time of writing, it appears as though the worst fears regarding supply disruptions may not be realized. Commodity prices have given back some of their recent gains, lowering risk premiums imbedded in market pricing. Moreover, the flow of natural gas to Europe has continued, even as Europe plots out a medium-term strategy to reduce its reliance on Russian imports.

Lockdowns in China to Hit Supply Chains This Spring

The start of the war realized a major global risk, but the pandemic continues to be an ever-present threat. As we recently highlighted, China’s commitment to a zero COVID strategy in the face of a highly contagious variant had the potential to impair supply chains anew. That risk too has been realized in recent weeks. Multiple cities have been locked down, including Shenzhen, a key location in electronic manufacturing and global transportation. As we saw in the early stages of the pandemic, a temporary shutdown has knock-on effects as order backlogs build up, resulting in strains on capacity. Even if authorities managed to quickly contain outbreaks and lift restrictions, the stoppages will add some sand in the wheels of global supply chains in the coming days and weeks.

Recently, authorities have experimented with modified ‘bubble’ like production environments, particularly in Shenzhen. In this arrangement workers live and work in the facility to limit exposure to the virus. Of course, only large manufacturing facilities with dormitories can implement these strategies, meaning that many of the smaller producers will remain offline, and transportation linkages between facilities remain strained.

March PMIs Provide First Look At Impacts Since the Outbreak of the War

Given the recency of the war in Ukraine, limited economic data are available to assess its impact. Moreover, the longer the conflict persists, the larger the effects will be. That said, the flash manufacturing PMI data for March, most of which were collected mid-month, provide an early glimpse of the economic impacts from the war. The indicators, and accompanying summaries, confirm expectations that the initial shock is being felt most in Europe, whereas the U.S. has been much more insulated.

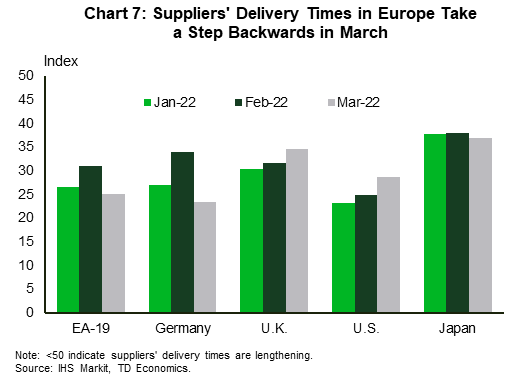

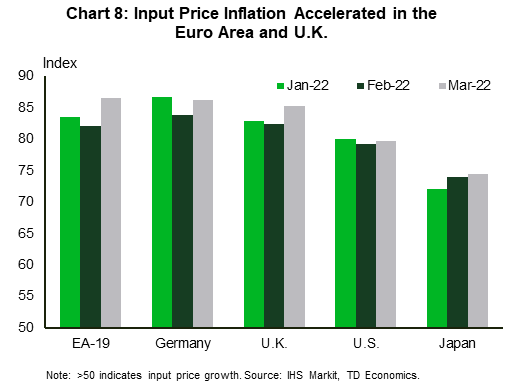

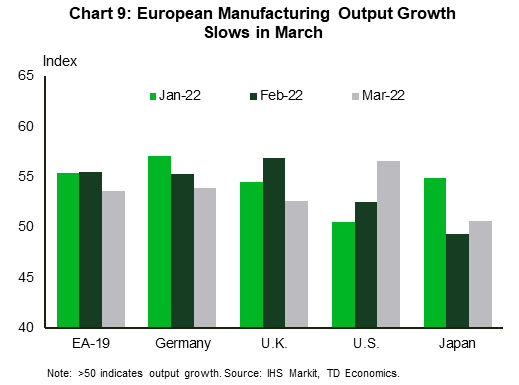

First, and possibly foremost, the manufacturers’ supplier delivery time indicator, after having steadily improved through the fall, took a meaningful step backwards in March (Chart 7). This corroborates anecdotal evidence of difficulties in sourcing supplies from Ukraine. Furthermore, the combination of scarcer supplies and spiking fuel, energy, and commodity costs have resulted in an uptick in input price inflation (Chart 8). Lastly, and most notably, manufacturing output growth (Chart 9) has accelerated sharply in the U.S. in March, as manufacturers cited improved supply chain and employment conditions. Conversely, the euro area and U.K. have witnessed a deceleration in output growth due, in part, to renewed difficulty in sourcing inputs and softening demand.

Again, these results are in line with the expected effect of the conflict. The war has provided a new snarl in logistics networks, raised input prices and impinged output. Layering on the uncertainty surrounding commodity markets adds another leg to input costs, prolonging the stagflationary force of the global supply shock.

Until goods demand cools, sustained improvement in supply chains will be a challenge

Forecasters are doing their best to incorporate the latest developments into their economic and inflation outlooks. In our recent QEF, we downgraded growth in the U.S., Canada and globally while inflation was further upgraded. While several scenarios could play out around the Russia/Ukraine war, we assume that peak uncertainty and stress in commodity markets extends into April, but then gradually declines.

With supplies for some commodities remaining scarce, there will be efforts to secure new supplies. For example, with the U.S. shutting out Russian petroleum imports, the U.S. is already in discussions with Venezuela about ramping up output and exports. Production in the U.S. and Canada is also likely to accelerate in the coming months on higher drilling. Still, in other areas – like grains – immediately finding alternatives won’t be easy. As they have been doing throughout the pandemic, companies will be further looking for ways to mitigate impacts of these latest shocks through continuing to diversify supplier sources, nearshoring some production to limit exposure to transportation bottlenecks, and even simplifying product designs1.

With regards to the role the U.S. consumer has had in the current situation, we’ve been waiting for the shift in demand from goods to services to bring relief to producers in North America and around the world. In the winter, goods demand – and for durables in particular – has started to level off. Durable goods consumption has fallen roughly 7.3% from its March 2021 peak as of January’s reading, having recovered some of the declines from December. More broadly, higher interest rates and the waning influence of fiscal stimulus will provide an additional drag on consumer demand – albeit with some small offset courtesy of substantial household savings. As prices are the product of both supply and demand, and in a world where supply is constrained, further declines in demand should hopefully help alleviate bottlenecks and price pressures, though the timetable on broad-based improvement now appears unlikely before H2-2022 and into 2023.

For some areas – notably semi-conductor intensive production – recovery could take longer. Based on industry estimates, 2021 investment in additional semi-conductor capacity likely won’t see equipment installed until 20232, meaning that the tight supply conditions are likely to persist through 20223. With roughly half of neon gas supplies going offline and unlikely to be resolved soon, near term relief looks to have slipped further from grasp.

Bottom Line

Putting it all together, timelines around a sustained improvement in supply chains have been pushed back yet again amid the war in Ukraine and COVID surge in China – to what extent, only time will tell. What is clearer to us is that so much will depend on how the demand side of the equation evolves in the coming months. If we’re right in our forecast, U.S. goods demand is poised to cool significantly in H2-22 and into 2023, helping to ease supply chains leaving them less vulnerable to supply-side hiccups.

References

- David J. Lynch, (Nov. 15, 2021) “As Supply Chains Strain, Some Corporations Rewrite Production Playbook”. Washinton Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/11/15/supply-chains-companies-strategy/

- SEMI. (June 22, 2021) “New Semiconductor Fabs to Spur Surge in Equipment Spending, Semi Reports.” https://www.semi.org/en/news-media-press/semi-press-releases/new-semiconductor-fabs-spur-surge-equipment-spending

- Aaron Aboagye, Burkacky O., Mahindroo A., Wiseman B., (Feb. 09, 2022) “When the Chips Are Down: How the Semiconductor Industry is Dealing with a Worldwide Shortage”. World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/semiconductor-chip-shortage-supply-chain/

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: