Questions? We've Got Answers

Addressing Issues Impacting the Economic and Financial Outlook

Date Published: February 12, 2026

The start of 2026 sparked plenty of economic shifts for our Q&A. From swings in the U.S. Dollar to President Trump's new nominee for Fed Chair, to various housing policy shifts under consideration on the U.S. side. Amidst it all, an economy once again displaying surprising strength. For Canada, questions address an economy continuing to adjust to U.S. tariffs, the upcoming CUSMA review, mortgage renewals and consumer impacts, and a stalling housing market recovery.

- Q1. 2026: Gold is hot, the Dollar's not. Is this expected to continue?

- Q2. Will the U.S. economy outperform peers…again?

- Q3. Will inflation ever feel normal again to Americans?

- Q4. What can we expect from a Warsh-led Fed?

- Q5. Can U.S. housing affordability initiatives lead to a lasting improvement?

- Q6. Canada's economy: another lukewarm year or cooling down?

- Q7. What might we expect in CUSMA negotiations?

- Q8. How is Canada progressing on doubling non-U.S. exports?

- Q9. What happened to mortgage renewal cliff fears and consumer impacts?

- Q10. When will Canada's housing market turn, or has it already?

Q1. 2026: Gold is hot, the Dollar's not. Is this expected to continue?

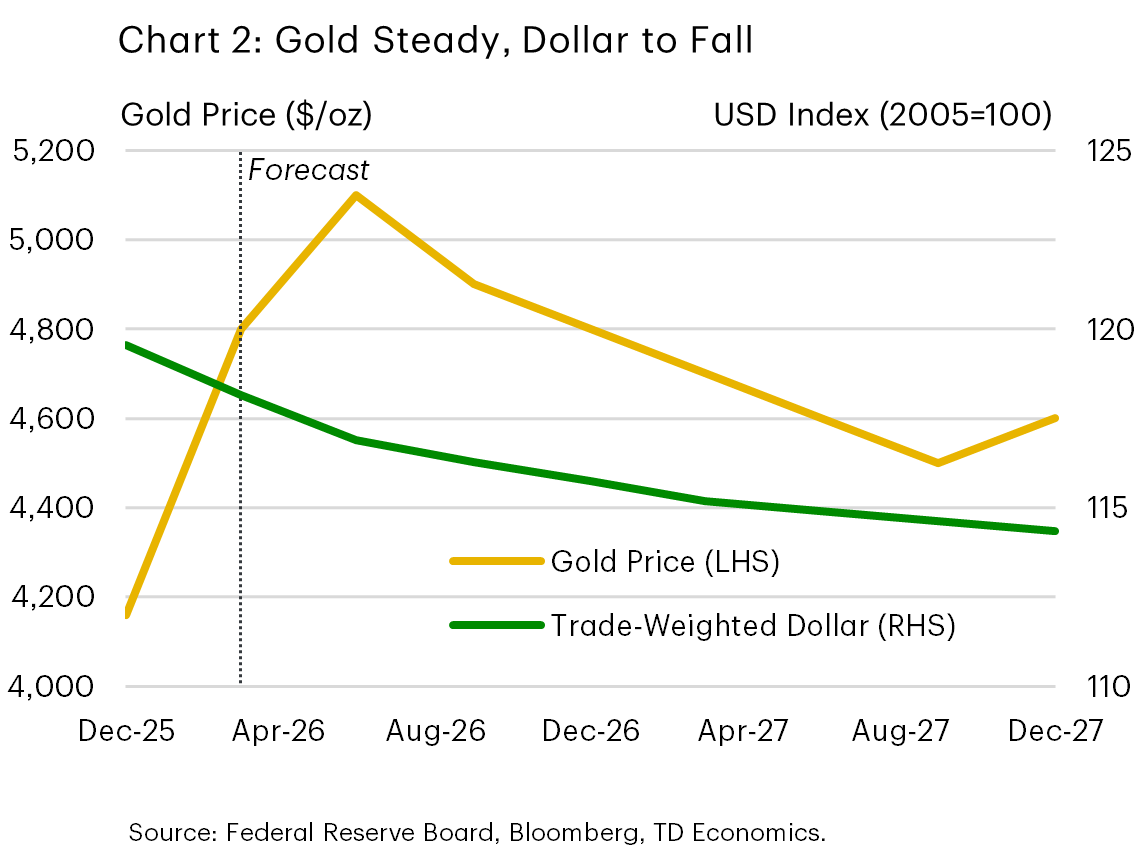

Sorta. The U.S. dollar (USD) faced a challenging year in 2025 and is still under pressure in the early weeks of 2026. Last year’s near-8% decline has further worsened to 9% on a broad trade-weighted basis. Meanwhile, gold surged past $5,000/oz, doubling its price from two years ago. We believe many of the factors that contributed to these dynamics in 2025 will remain relevant in 2026. However, since these factors are already reflected in the pricing, a repeat performance in 2026 is unlikely absent the introduction of new geopolitical or domestic dynamics.

Several factors collided to weaken the USD in the first half of last year: the "Liberation Day" tariffs, budget deficit concerns tied to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and worries around Fed independence. The other side of this was investors pursuing alternative safe havens – like gold.

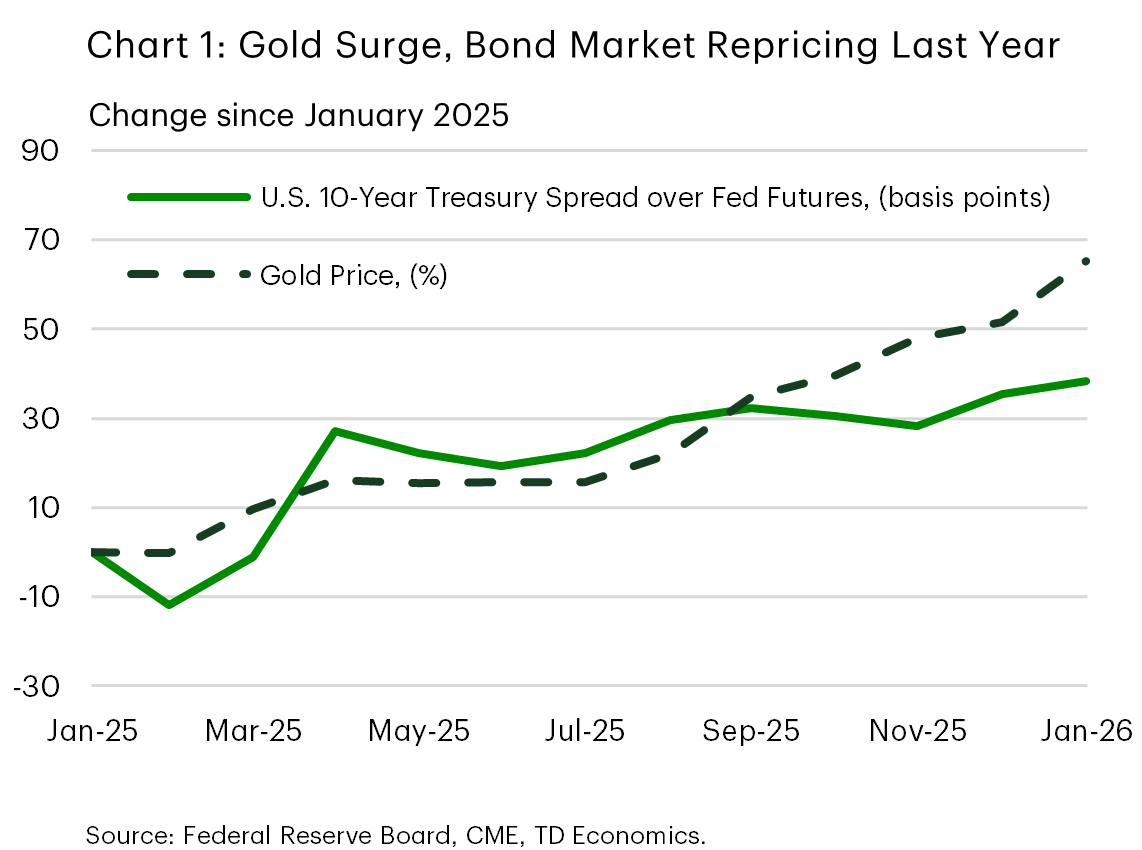

The sentiment shift was also noticeable on the U.S. 10-year treasury yield, which hung higher even as expectations grew for Federal Reserve rate cuts (Chart 1). It’s less common to see a run-up in gold prices alongside a steepening yield curve, driven by the combination of falling short-rate expectations and stubborn long-term yields. Normally "safe haven" flows benefit both gold and U.S. treasury yields, shifting the curve down, rather than steepening it. However, it was clear investors preferred alternatives, which saw flows into the Swedish krona, Swiss franc, pound sterling, and euro, for the same host of reasons that led to a steepening of the yield curve.

Enter 2026. The topic of discussion is different but not the broad issue or sentiment. January saw the broad USD depreciate during the week of the Davos conference, when geopolitical tensions surrounding the United States' interest in Greenland threatened to blow up their trade agreement with the European Union and ratchet tariffs higher yet again. This was compounded by talk from European investors and institutions about selling their U.S. dollar assets. While easier said than done for holders of U.S. assets, the return of heightened trade uncertainty and another crack in the greenback's safe haven armour was enough to send the USD down further.

Meanwhile, emerging market central banks—especially in China, India, the Middle East, and ASEAN—have accelerated gold purchases as part of a strategic shift in reserve policy, contributing to gold prices soaring more than 60% over 2025. Looking forward, gold’s outlook remains positive, but price gains are likely to moderate absent supply constraints in the gold market or another major geopolitical catalyst. We expect gold could breach $5,000/oz again next quarter before settling down and ending the year around $4,800/oz, near its price today.

For the Canadian dollar, the ongoing U.S. dollar weakness supports a medium-term target of 0.74–0.75 by year-end, driven by narrowing interest rate gaps. The U.S. dollar has already hit our mid-year forecast, but asset prices tend to move in fits and starts, so this is no indication that it will continue to decline at this pace. We continue to forecast a broad depreciation of 3% for the USD by the end of 2027 (Chart 2). But uncertainty and the potential for more abrupt moves remain high, and another bout of geopolitical turmoil could push the U.S. dollar temporarily below our projections.

Q2. Will the U.S. economy outperform peers…again?

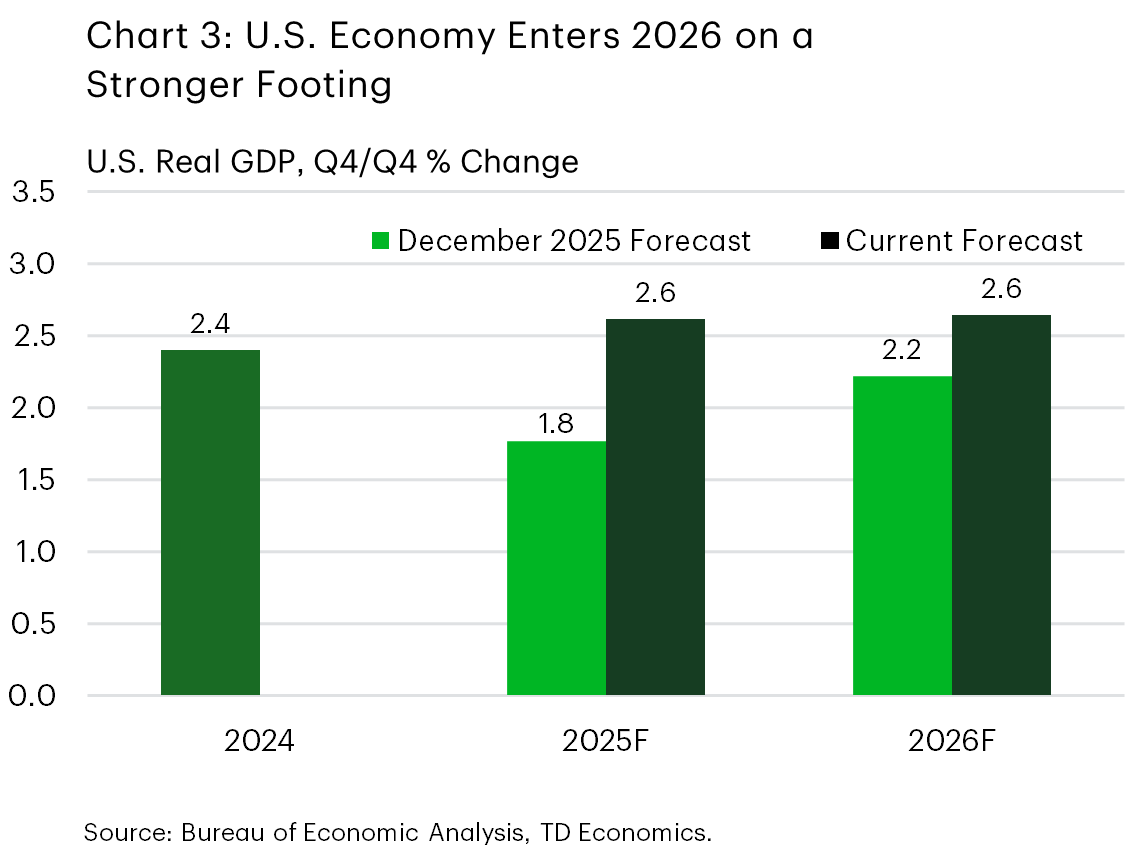

Yes, and likely by a wide margin! Since our forecast in mid-December, there have been significant upward revisions to the U.S. outlook. In large part, this reflects stronger momentum coming out of 2025, aided by sustained strength in AI investments and a pick-up in consumer spending. The recent government shutdown has delayed the release of Q4 GDP data, but that growth is tracking around 3% with the components that are known. If so, 2025 will have ended with stronger momentum than in 2024, by roughly two-tenths at 2.6% on a Q4/Q4 basis (Chart 3). This is nothing short of impressive given the overhanging cloud of heightened trade uncertainty and a fed funds rate well in restrictive territory for nearly the entirety of the year! We anticipate that momentum will largely hold in 2026, with an economy at 2.6% (Q4/Q4). This is four ticks higher than our forecast in December and well ahead of peer economies.

This year begins with a fiscal tailwind. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) included several new tax deductions for households, which were retroactive through 2025. Since the IRS didn't update its withholding tables until this year, many tax filers will benefit from larger refunds. According to estimates by the Tax Foundation, 2025 OBBBA refunds could be as high as $129 billon – or roughly $1,000 higher per tax-filer. Historically, about half of all refunds are paid by the end of the first quarter, and three quarters of the payments roll out by Q2. Additionally, households are benefiting from higher take-home pay. The combined effects are expected to lift after-tax household income by over $200 billion this year, creating a material tailwind for consumer spending through 2026 (see report). While the breaks skew to higher income taxpayers, conservative multipliers still lift nationwide consumer spending by several tenths of a percentage point.

Beyond the individual tax cuts, the OBBBA also changed several business-side provisions including full bonus depreciation on equipment, full expensing for research & development costs, temporary expensing for manufacturing structures and a more generous business interest deduction. Combined with a backdrop of easier financial conditions, some easing on regulation, and trade uncertainty taking less of a toll on decision making, we believe these measures will help broaden business investment beyond AI.

Q3. Will inflation ever feel normal again to Americans?

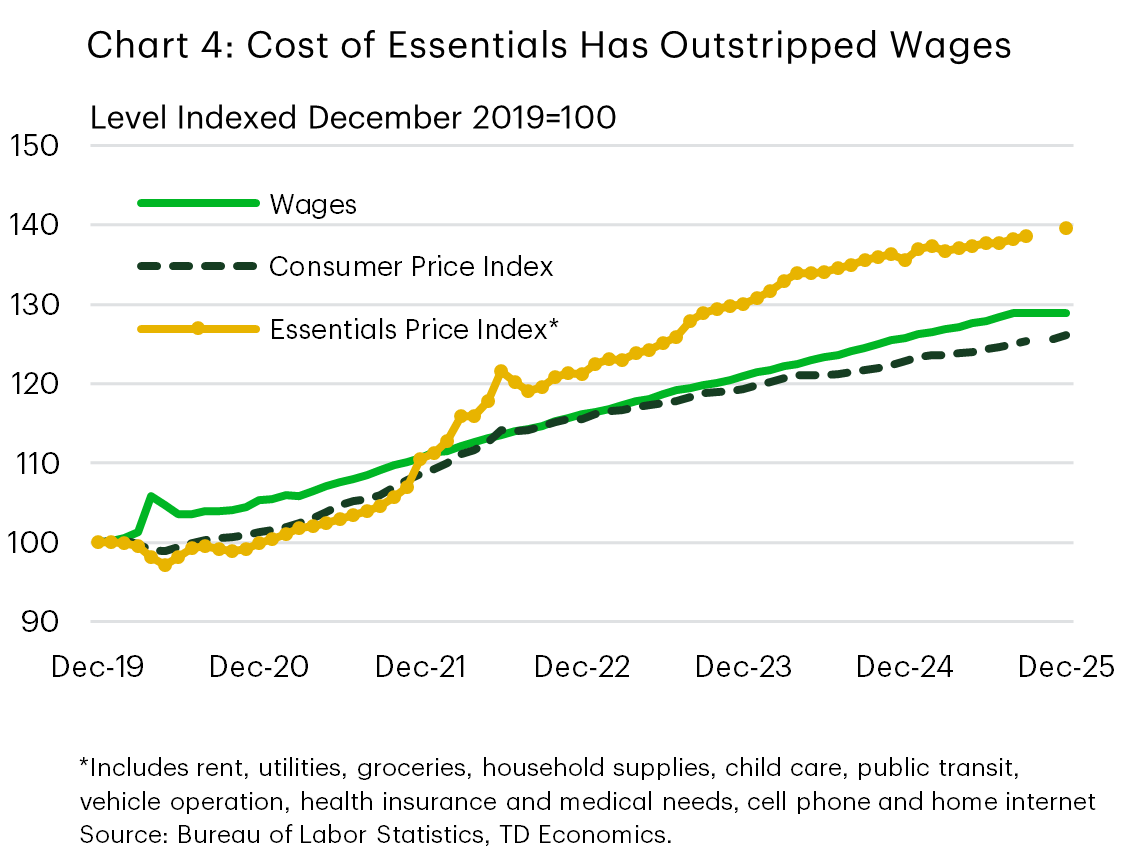

High prices are a top concern for Americans. Inflation has come down from the post-pandemic surge, but there has been little further improvement over the past year. Zeroing in on prices for everyday essentials, the gap relative to wage growth remains wide (Chart 4). This has been particularly punishing for lower-and-middle income households, since these essentials make up a larger share of their budgets.

Unfortunately, these pressures are unlikely to meaningfully abate this year. We expect the cost of tariffs to increasingly show up in consumer prices over the near-term. If corporations use the new calendar year as an opportunity to reset prices on goods, it will limit any further disinflationary pressure from the services side. Core measures of inflation are likely to hover at 3% through most of this year.

And, we have reservations about the sustainability of the recent disinflationary pressure on services inflation. Some of the cooling through late-2025 came from a sharp slowdown in shelter costs. This may have been due to BLS stop-gap measures when they were unable to collect data on rents during the government shutdown. The November estimates were considerably lower than the months prior, lessening shelter's contribution to overall inflation. The effects of this adjusted methodology could linger on shelter prices – albeit with a diminishing influence – for up to six-months before the sample panel for rents resets.

We expect core inflation to return to the Fed's 2% target by the end of 2026 on a quarter/quarter basis. However, it will take longer for prices to feel "normal" to consumers. Inflation is a measure of growth, not levels. Slower inflation still means that prices are climbing and not returning to levels consumers remember or would like to see. It will likely take more time for the sticker shock to wear off, and for the higher price level to seem normal.

Q4. What can we expect from a Warsh-led Fed?

After many months of deliberation, President Trump nominated Kevin Warsh to be the next Chair of the Federal Reserve. However, there's some uncertainty surrounding his confirmation. Warsh's nomination must be vetted by the Senate Banking Committee, which includes Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC) who has said that he would block President Trump's nominee until the Justice Department's probe into Fed Chair Powell is "fully and transparently resolved." The President has responded by saying that he could delay Warsh's confirmation until after Tillis leaves his post in January 2027. If this were to happen, Jerome Powell would likely remain as acting Chair, or the Board could pick a new acting chair – presumably Vice Chair Philip Jefferson - until Warsh is confirmed by the Senate.

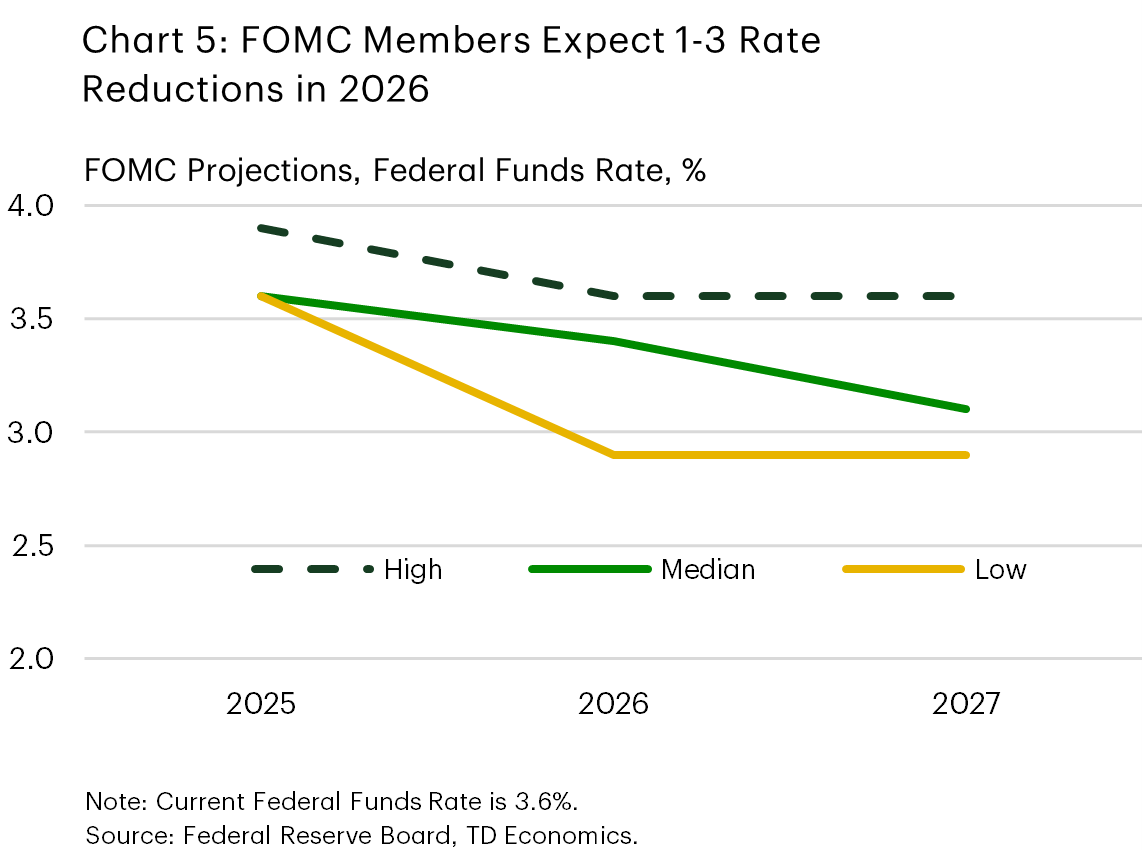

Warsh brings plenty of experience to the role, including a 5-year term as a Federal Reserve Governor (2006-2011). However, the task of building consensus among the committee members as a newcomer to the current board could take time. This means that his views on monetary policy will be considered amid the balance of opinion of the voting members of the FOMC, which is still skewed towards limited rate reductions in 2026. The December Summary of Economic Projections showed the median expectation of FOMC members was for a single rate cut in 2026 (Chart 5), despite financial markets with two cuts priced into the futures market.

Recent economic developments have supported the Fed's decision to stand still on interest rates. The economy has strengthened, the unemployment rate has steadied, and a persistent moderation in inflationary pressures is not assured. The central bank approaches interest rate cuts through a lens of "risk management". And right now, the urgency is lacking.

However, the level of the federal funds rate is still slightly restrictive towards economic growth, giving the Fed runway to pause to ensure inflationary pressures remained tapped down before nudging rates into a “neutral” stance. Our base case forecast assumes another 50 basis-points of policy easing by year-end. However, this is conditional on the effects of tariffs fading and inflation showing more definitive signs of moving back towards the Fed's 2% target, particularly with economic momentum showing more of a tailwind than previously assumed.

Q5. Can U.S. housing affordability initiatives lead to a lasting improvement?

The U.S. administration is considering a wide range of policies to improve housing affordability. So far, the emphasis skews toward demand-side measures including allowing longer mortgage amortizations (e.g., to 50 years), purchasing mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to lower mortgage rates, and expanding access to retirement funds for down payments. Each measure is likely to have a modest impact on its own, but the combination could increase demand among homebuyers more notably.

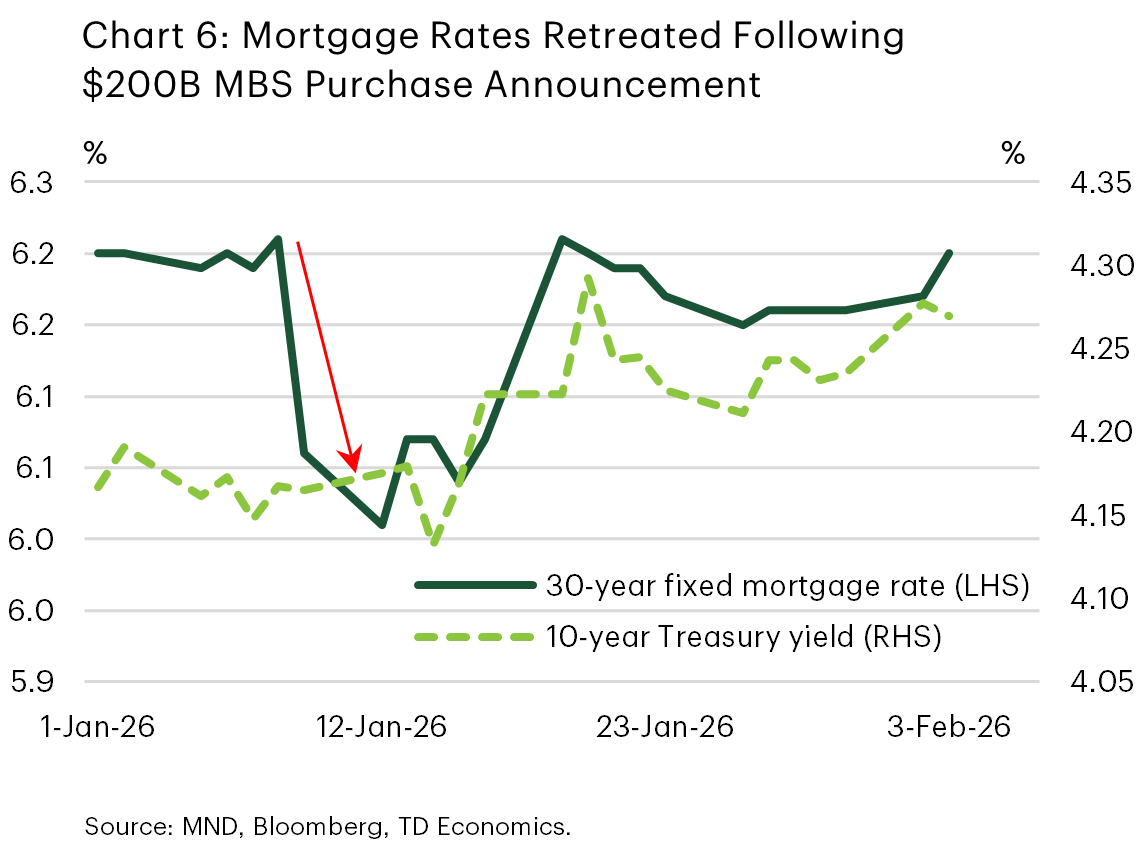

Measures to boost demand tend to be quicker to implement and bear fruit than those that increase housing supply. For example, mortgage rates dropped immediately following the announcement of the MBS purchase policy in January (Chart 6). However, absent a parallel response in housing supply, increased demand risks pressuring home prices higher, eroding the intended affordability gains over time.

Options to increase housing supply include easing regulatory barriers, reducing the capital gains tax for home sales, and zoning reform. If successful, affordability would improve by moderating house price growth relative to income. However, even though a few regulatory changes could be implemented quickly through executive action, housing supply in general tends to respond slowly and with longer timelines. This means that, in the near-term, the boost to demand through policy measures could dominate housing market dynamics. For more detail, see our recent report here.

Q6. Canada's economy: another lukewarm year or cooling down?

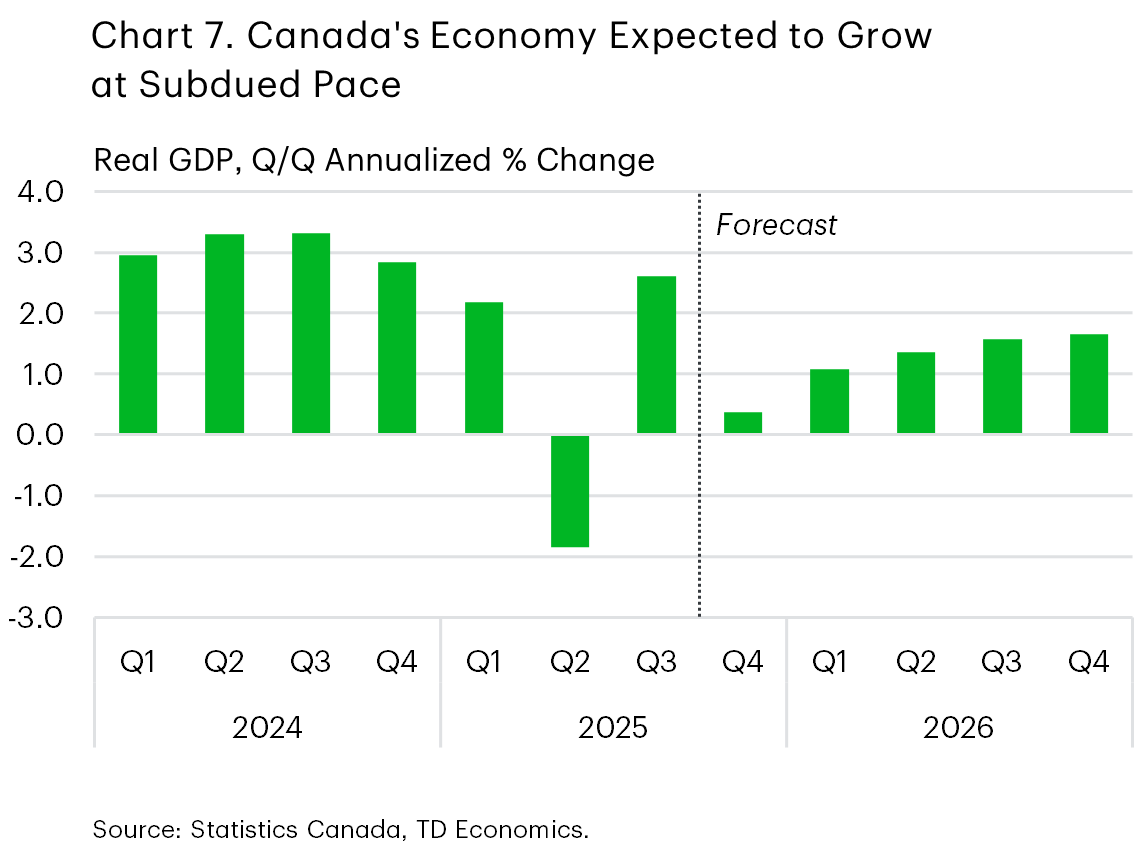

The economic temperature for Canada will be lukewarm in 2026, but with a little more heat turned up by the end of the year. We anticipate the year will end with an economy 1.4% larger than 2025, which doesn’t sound like much but would be an improved pace from last year’s 0.8% pace. (Chart 7). Greater government's spending and ongoing household income gains support activity. In addition, we anticipate that the worst effects of the trade shock have faded – but this comes with a high degree of uncertainty as the CUSMA review ramps up (see Question 7).

Of course, business investment will still feel the weight of trade uncertainty and the gradual rotation of exports to new markets. And a shrinking population will weigh on employment growth, limiting the speed of recovery to housing demand and spending. All together, we anticipate little job growth in the first half of the year. In normal times, zero employment growth would ring the alarm bell. However, fewer available workers will dominate the direction of the unemployment rate. Limited slack in the labour market should prompt its very gradual decline through the year. This dynamic was evident in January, when a drop in employment was met with a drop in the unemployment rate.

Q7. What might we expect in CUSMA negotiations?

The CUSMA/USMCA review is shaped by three major considerations:

- The U.S. negotiating agenda.

- The legal ambiguities within the U.S. on withdrawal authority.

- The uncertainty about what trade framework would govern Canada–U.S. commerce if the agreement was terminated.

The United States will drive the parameters of the review. Testimony from U.S. Trade Representative, Jamison Greer, outlined several longstanding asks of Canada, including expanded dairy market access, concerns related to Canada’s Online Streaming and Online News Acts, provincial restrictions on U.S. alcohol sales, government procurement limitations in several provinces, burdensome customs registration processes, and issues surrounding Alberta’s electricity imports from Montana.

Beyond bilateral issues, the U.S. is seeking a laundry list of joint commitments from both Canada and Mexico. These include tighter rules of origin for nonautomotive industrial goods, deeper alignment on economic security tools such as tariffs and export controls, mechanisms to discourage offshoring of U.S. production into Canada or Mexico, setting up a regional Critical Minerals Marketplace, and strengthening the enforcement of labour requirements. Addressing these issues will require complex negotiations, especially within Canada’s broader trade diversification strategy.

For now, our expectations are that the status quo prevails – CUSMA continues to provide cover for most Canadian goods, with Section 232 tariffs applying to select products. However, it is important to analyze all scenarios, including the risk the agreement is terminated entirely.

If a country seeks to withdraw, it must provide 180 days’ written notice. In the U.S., "who" has the authority to withdraw is murky: the Senate Finance Committee argues congressional approval is necessary, while the Congressional Research Office suggests the President may hold greater unilateral authority. Litigation is likely to occur if the President unilaterally announces a withdrawal, adding significant uncertainty. For Canadian businesses, the uncertainty extends further: it is unclear which trading rules would apply if CUSMA ended. Would the original Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement (1988 FTA) that was suspended but not terminated come back into force?

If CUSMA were terminated, and the 1988 FTA is not in force, Canadian exports could face a 35% tariff under IEEPA. However, this too is pending a U.S. Supreme Court decision. In the event that those tariffs are removed, selected goods would continue to face the higher 25–50% rates imposed under Section 232. These levels would serve as the basis for future negotiations, which could mirror deals struck between the U.S. and other partners that traded tariff relief for concessions on quotas, reduced regulatory barriers, and energy purchase and investment commitments. However, it’s evident that all roads lead to persistent business uncertainty among Canadian exporters. This is all it takes to keep a restraint on investment growth.

Q8. How is Canada progressing on doubling non-U.S. exports?

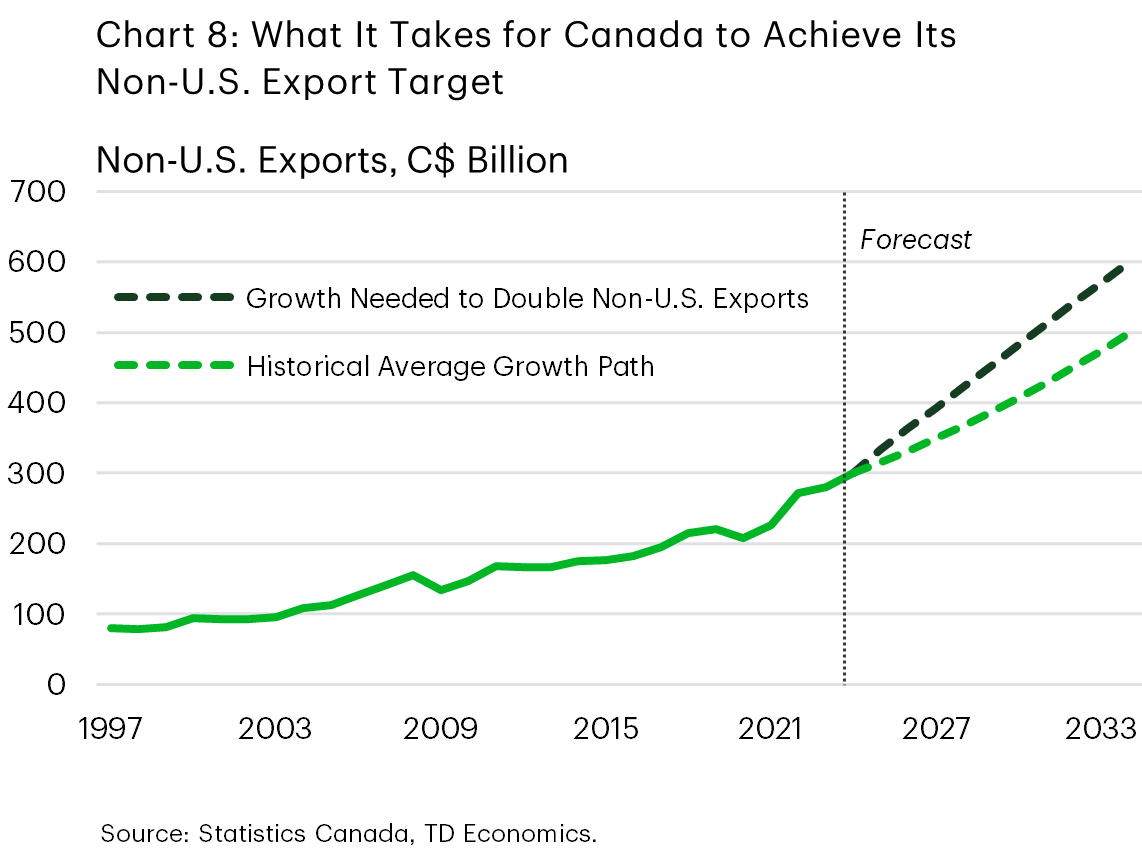

Last year, the federal government set a goal to double the value of exports to countries outside the United States over the next decade. Achieving this is ambitious, as it requires boosting exports of both goods and services to non-U.S. partners by about $300 billion, equivalent to 7% growth annually for ten years. This would raise the share of non-U.S. exports to roughly 35%, compared to approximately 25% historically (assuming exports to the U.S. revert to their historic growth rate of around 4%). Progress has already begun, with trade to non-U.S. countries growing by more than 11% in 2025. But sustaining this pace will be difficult. (Chart 8).

First, last year’s performance benefited from the meteoric rise in gold prices, responsible for about one-third of that growth. As noted in question 1, we don’t anticipate a repeat performance or one that is sustained for the coming decade. Second, up until now, diversification has mainly involved selling existing products to current partners. As an example, in 2025, oil and LNG shipments to Asia and Europe rose by a healthy 25%. But sustaining robust growth depends on whether pipeline and export capacity can be scaled up. The same is true elsewhere.

Canada must go beyond just leaning further into energy. It must also leverage other areas of strength such as critical minerals, mining, and agriculture. However, this requires an increase in export capacity at ports, rail lines, and other trade-enabling infrastructure. In turn, this requires an increase in private capital and a further acceleration in the regulatory approval process across all stages of development.

Q9. What happened to mortgage renewal cliff fears and consumer impacts?

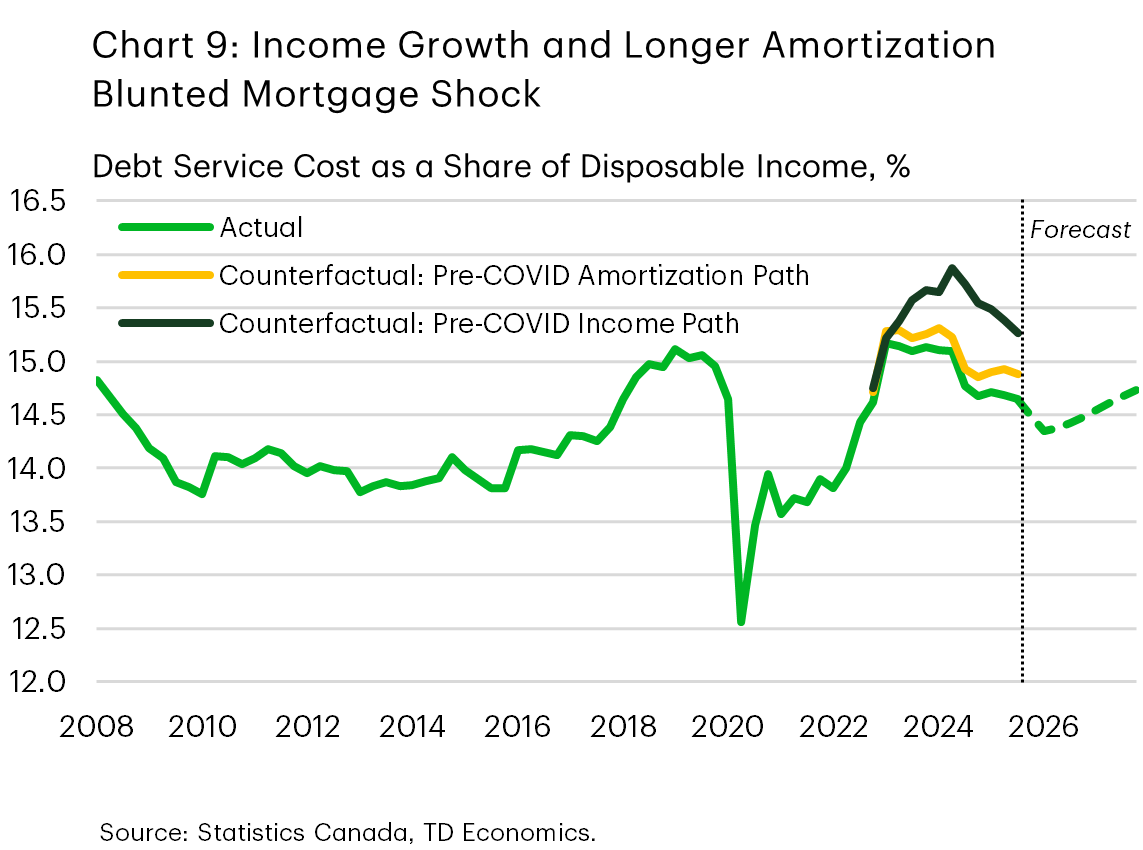

One worry hanging over the Canadian consumer is that spending will be held back due to increased mortgage payments as mortgages originated at rock-bottom pandemic interest rates renew into higher prevailing rates over the coming quarters. A Bank of Canada analysis of 2025-26 renewals show that 15% of outstanding mortgages will see payments increase in 2026. Most of these are five-year, fixed rate mortgages, and affected borrowers could see payments increase 20%, depending on whether they adjust their amortization length.

These figures might give readers pause, but there’s more going on beneath the surface that is expected to leave a much smaller mark on overall consumer spending. In particular, the debt service ratio for the economy is below its recent highs in 2023, suggesting the period for the worst risk has already past (Chart 9). This lower debt servicing burden exists for two reasons: healthy income growth and longer amortizations. The average mortgage amortization has been rising since early 2021 and now sits about 16 months longer than before the pandemic. This has helped lower aggregate debt payments and smooth the payment shock against rising interest rates in 2022 and 2023, though it was not the dominant driver.

The more important factor has been stronger growth in personal disposable income. This has turned a mortgage “cliff” into a much gentler "hill". Over the past three years, personal disposable income growth has been roughly two percentage points faster than in the three years preceding the pandemic. Had income growth instead tracked that pace, the debt service ratio – the share of income devoted to debt servicing – would have peaked about one percentage point higher (Chart 9). In other words, faster income growth cushioned a meaningful share of the interest rate shock.

That income strength also helped to boost the savings rate moderately above trend, providing another cushion for Canadian consumers. Looking ahead, we expect downward pressure on aggregate debt payments as lower policy rates gradually feed through to debt-servicing costs – a process that historically takes four to six quarters. These factors should help support modest consumer spending this year.

Q10. When will Canada's housing market turn, or has it already?

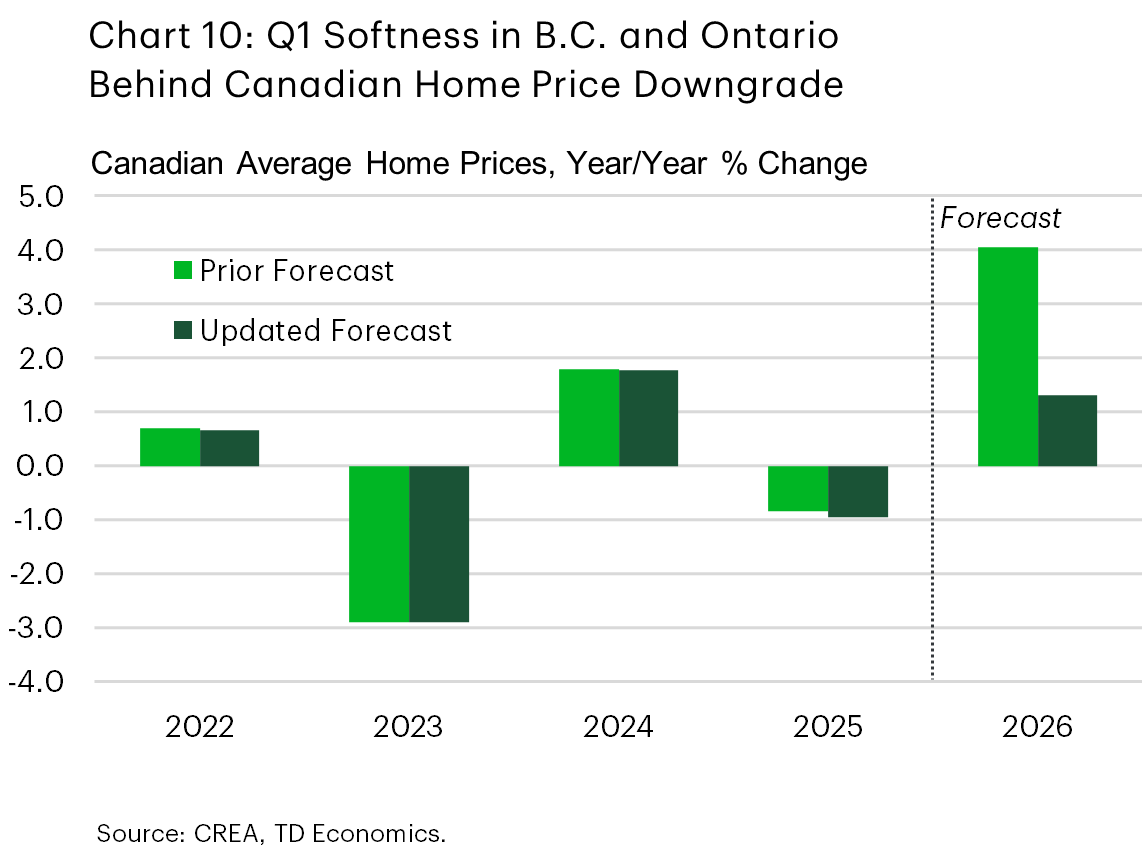

The market hasn’t turned yet. Recent data show a weaker-than-expected first quarter for home sales and prices, especially in B.C. and Ontario. This is partly due to January storms, but even accounting for some rebound, the sharp Q1 pullback has led us to downgrade the 2026 outlook (Chart 10). Canadian average home price growth is likely to be closer to 1% rather than the 4% expected in our December outlook.

The modest 1% price gain at the national level is still consistent with a gradual, modest recovery supported by pent-up demand. However, a strong rebound looks unlikely given multiple headwinds: elevated supply in key regions, slow population growth, softer labour markets, and still stretched (but improving) affordability in Ontario and B.C.

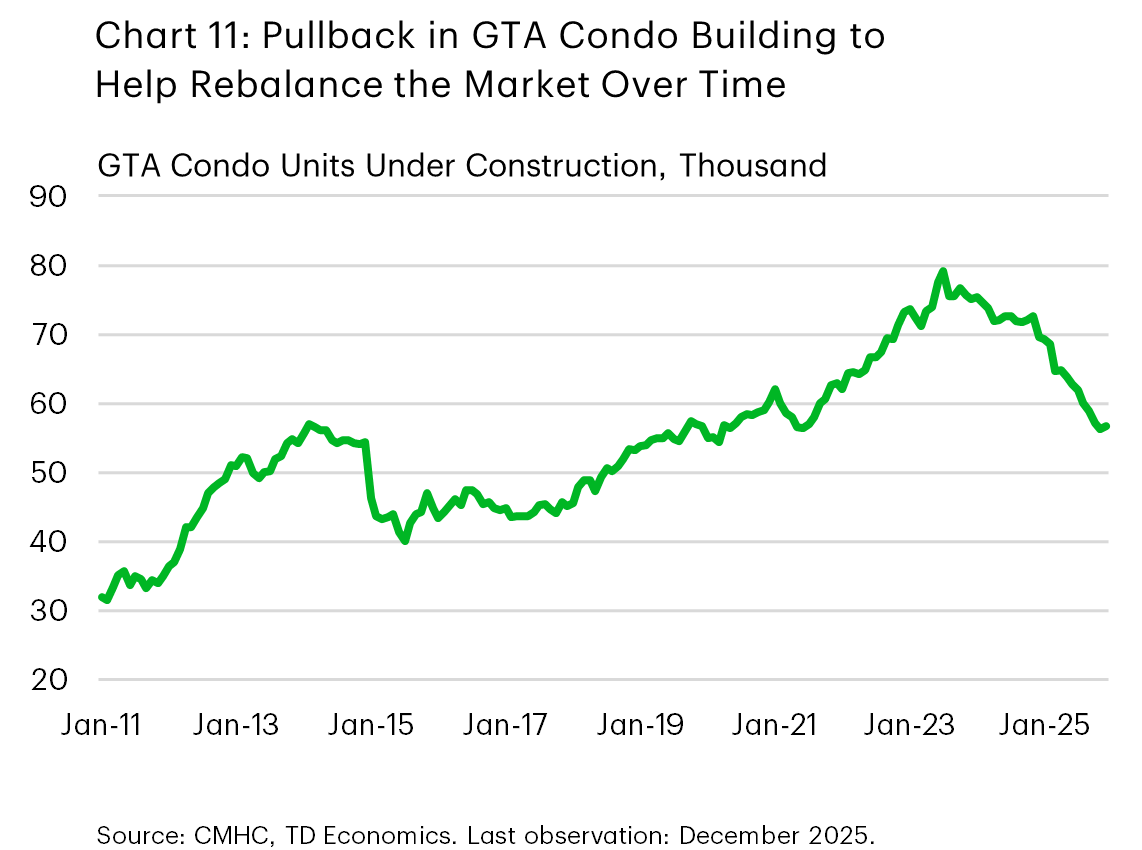

Conditions should improve in 2027 in parallel with an improvement in the economy and affordability, particularly within the B.C. and Ontario markets. After that, a return to modest population growth should lend a helping hand in 2028 or 2029. Supply should also continue to tighten with construction activity sidelined in key over-supplied regions, like the GTA condo market, which is famously the weakest market in the country (Chart 11).

In terms of risks, economic underperformance poses a downside risk. However, upside potential also exists if falling prices unleash the significant pent-up demand that exists within Ontario and B.C. faster than we expect. We have seen this before in Canada when periods of surging home sales caught many forecasters off-guard in 2023 and 2024.

For any media enquiries please contact Oriana Kobelak at 416-982-8061

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.