Highlights

- China's successful containment of the virus and the government's investment-driven stimulus has helped it recover faster from the pandemic than other economies.

- China's merchandise trade, portfolio inflows (equities and debt), currency and stock market have long crossed pre-pandemic levels. China has also done better than most countries in terms of FDI inflows.

- These developments will likely give China even more economic clout and allow it to exert greater influence on global and regional geopolitics. With that may come an even greater likelihood of conflict with its rivals in North America and Europe.

What a difference a year can make! Just over twelve months ago the world's first COVID-19 death was reported in China. That was only the start of what soon became an unprecedented global economic and health disaster. The virus has taught economists many lessons along the way. One of the most important lessons being that virus containment and sustainable economic recovery go hand in hand. China learned that lesson early in the crisis and successfully contained the virus and resumed economic activity, while North America and Europe continue to struggle.

China's merchandise trade, portfolio inflows (equities and debt), currency and stock market have long crossed pre-pandemic levels. China has also done better than most countries in terms of FDI inflows. These developments will likely give China greater economic clout on the global stage in the coming years and allow it to exert greater influence on global and regional geopolitics. With that may come an even greater likelihood of conflict with its rivals in North America and Europe.

China's Control Of The Virus Has Aided Its Recovery

The Chinese government’s investment-driven stimulus has helped China recover faster than other countries (see report). In fact, China is the only major economy that is expected to register positive growth (+1.8%) in 2020. Earlier concerns about an uneven recovery – strong investment, weak consumption – have also abated, as the Chinese consumer has made a strong comeback. Chinese consumption has now been higher than year-ago levels for four straight months.

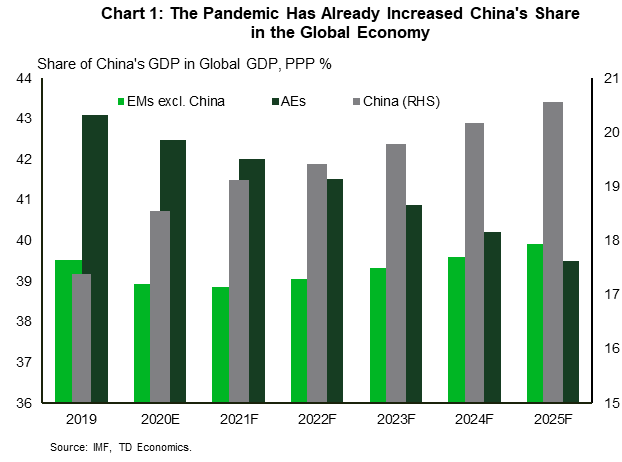

China's strong recovery has increased its share in the global economy. Before the pandemic, China's economy had been slowing down for some years (aging population, rebalancing the economy from investment to consumption etc.), but the pandemic has changed that. China’s share of global output in 2021 is expected to jump to around 19% in 2021 – 1.7 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic level and above where it would have been in the counterfactual no-COVID world (Chart 1). By 2025, China's share in the global economy is expected to cross 20%, while U.S.' share is forecast to shrink from 15.9% in 2019 to 14.8% by 2025.

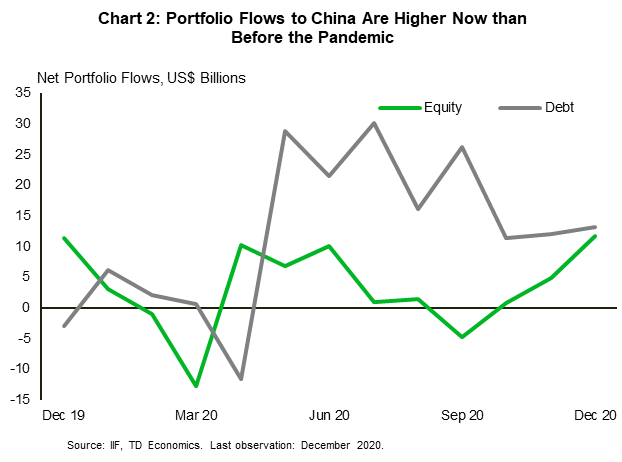

Global investors – who are hungry for returns in this world of rock bottom interest rates – are struggling to find their footing elsewhere so are seeing tremendous potential in China. The Chinese government had also put in place incentives to retain and attract new investment soon after the pandemic hit, which limited capital outflows.

Net portfolio flows to China are already higher than pre-pandemic levels, reflecting investors' upbeat sentiment about the country's recovery prospects (Chart 2). In fact, earlier this month, Chinese stocks closed at their highest level since the global financial crisis in 2008. The country's stock market has so far outpaced the rest of the world (including the U.S.). China’s CSI 300 has rallied about 32% since the beginning of last year, compared to 17% for the S&P 500. And while retail investors – the traditional backbone of the Chinese stock market – remain important for Chinese equities, institutional investors are now playing an increasingly important role. This has helped reduce Chinese stock market volatility, making it more attractive for foreign investors.

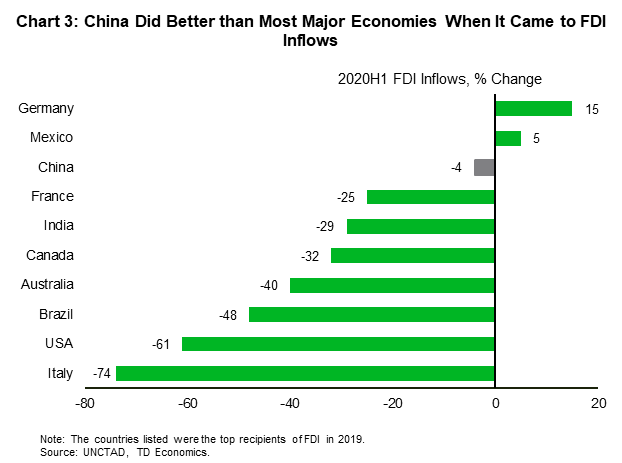

China has also done better than the rest of the world in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows (Chart 3). While global FDI – a measure of globalization and economic confidence – fell 49% in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, flows to China only contracted by 4% (U.S. and Canada contracted by 61% and 32%, respectively).

Meanwhile, a combination of China's strong economic recovery, foreign central banks moves to slash interest rates and Joe Biden's election victory has boosted the Chinese renminbi. Earlier this month, the renminbi rallied to its highest level in more than two years, making up for losses suffered since the US-China trade war. The onshore renminbi crossed the 6.5 per dollar threshold for the first time since 2018.

On the fiscal front, China's discretionary fiscal spending in response to the pandemic has only been 4.7% of GDP. Therefore, unlike several major economies, China has ample fiscal space to have "moderately supportive fiscal and monetary policies until the recovery is on solid ground" according to the IMF.1 This gives China a leg-up on other countries, many of whom have seen debt levels hit new highs due to the pandemic.

China's robust recovery has been powered by its Government-backed investment, especially in new technologies. This is in line with China's aim to move towards high quality growth and higher value-added exports and emerge as a global technological powerhouse in the coming years. Under the Government's latest 5-year plan, the country aims to be self-reliant in technology.

{related-articles-row}

Is China Eating Others' Lunch?

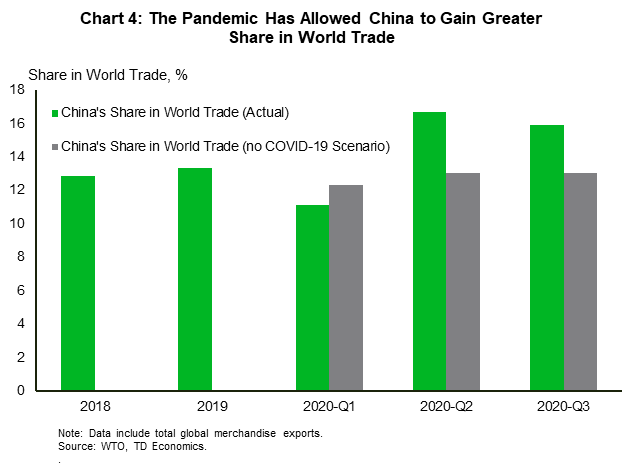

In the first quarter of last year, China's share in world trade dropped, since the pandemic hit the country (in January and February) before any other nation.2 But as China recovered, so did its trade. Notwithstanding the strong renminbi, it's share of global trade rose sharply in the second quarter of last year. The latest data show that China's share has jumped to about 16% – three percentage points more than it would have been without the pandemic (Chart 4). The pandemic has also allowed China to capture greater global market share. Early in the pandemic, China's exports rose on the back of global demand for its medical supplies and related equipment. More recently, however, the country's exports have been increasing across the spectrum of product categories. It would be difficult for other countries to unseat China even after the pandemic is over, now that it has captured others' market share.

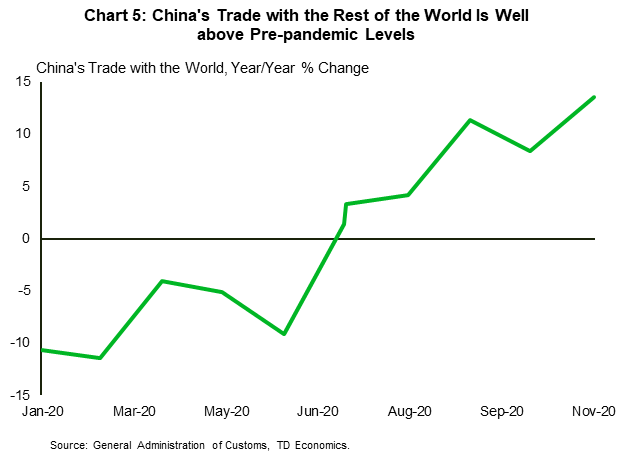

China’s trade has also done well relative to other countries. In the U.S., exports remain almost 13% below last-year levels.3 In the European Union, exports and imports are 9% and 11%, respectively, below year-ago levels. China’s trade with the rest of the world is already well above pre-pandemic levels and has grown on average 7% (year-on-year) over the past six months (Chart 5). These developments combined have pushed China’s trade surplus to record highs. China's trade surplus for the first 11 months of last year was $460 billion, up by a fifth. This shows the extent to which the pandemic has forced countries to increasingly rely on Chinese goods. The ongoing restrictions – and in some cases lockdowns – in some Western economies means that they are producing and exporting less, therefore, relying more on imports.

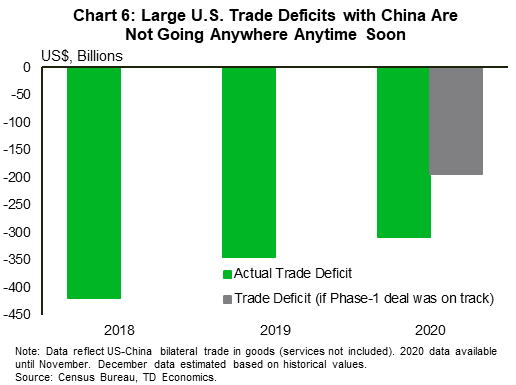

Meanwhile, China's trade surplus with the U.S. continues to swell this year, despite the Trump administration's efforts to rebalance trade in U.S.' favour (Chart 6). Meanwhile, China's import targets under the Phase-One deal – which were too ambitious to begin with – haven't been helped by the pandemic. Early last year we had said it would be extremely difficult for China to meet its Phase One deal targets, and we seem to have been right (see report). Through the first 11 months of last year, China's purchases of all products covered in the deal were only 58% of their year-to-date targets. It is now impossible for China to meet its Phase-One deal targets for 2020. The U.S. may slap more tariffs on China for failing to meet the deal's targets, but there is a limit to imposing tariffs on another country (China) before it starts hurting the country (i.e., the U.S.) imposing them. America's trade deficits with its arch-rival are here to stay. President-elect Biden's team has got their work cut out for them.

China Is On Collision Course With Other Powers

China's curtailment of the virus and robust recovery has opened the door for increasing influence on the global stage. It has also put China on collision course with its rivals. For example, last November, the EU had proposed a fresh alliance with the U.S. to meet the "strategic challenge" posed by China; the French Finance Minister separately said that “We have to decrease our dependence on a couple of large powers, in particular China”; Japan is also looking into ways to break supply chain dependence on China and is paying firms to relocate out of China.

However, this has not stopped western nations from signing economic deals with China at a time when they are still deeply mired in the crisis. For example, the EU recently signed an investment treaty with China, much to the dismay of human rights advocates. The deal – which is also likely to create friction with the Biden administration – will allow Chinese companies to make new inroads into Europe.

China – under Xi Jinping – was becoming increasingly assertive in recent years anyway, but the pandemic has exacerbated that. China's strong recovery will only increase its dominance going forward. Notwithstanding a Biden presidency, China's tensions with its rivals in North America/Europe are likely to increase. Therefore, companies are wary of being caught in the crossfire between China and their home country, prompting them to pull out of China when they can. But while relocating out of China may be possible for big companies (the Apples of the world), it is less feasible for smaller companies. Many companies might want to relocate but wouldn't be able to due to China's tight grip on global supply chains.

Bottom Line

China has successfully contained the virus, while North American and European economies are still faced with tight restrictions on the back of rising caseloads and hospitalizations. China's investment-driven stimulus has helped it recover faster than other countries. It's merchandise trade, portfolio inflows (equities and debt), currency and stock market have long crossed pre-pandemic levels. China has also done better than most countries in terms of FDI inflows. This will give China more influence at the global stage and allow it to exercise greater clout on global and regional geopolitics. China's rivals are uneasy but will have to contend with its rising power. Expect greater conflict between China and its rivals – especially the U.S. – in the coming years. Afterall, China and the U.S. are the perfect example of being stuck in a Thucydides Trap – a conflict between an existing power being challenged by an upcoming power.

End Notes

- https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2021/01/06/Peoples-Republic-of-China-2020-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-49992

- There is also a seasonal slowing down in China in Q1 every year.

- In November, U.S. imports crossed year ago levels for the first time since the pandemic onset, registering 0.3% growth.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: