Imminent Russia Debt Default Has Not Unsettled Financials Markets?

Doug Hostland, AVP | 416-307-7532

Faisal Faisal, CFA, Manager | 416-983-1738

Date Published: April 4, 2022

- Category:

- Global

- Global Economics

Highlights

- Financial markets are braced for Russia to default on its sovereign debt. But as of yet there are no signs of contagion. Emerging market equity and bond prices are unfazed.

- This is not surprising, given that foreign investors hold only around $20 billion in Eurobonds issued by the Russian government which is small relative to overall exposures. Also, $20 billion would not rank high on the list of major sovereign debt default episodes.

- In the event of a default, debt restructuring negotiations would not begin anytime soon and would likely drag on for a long time. In the meantime, the inability of the Russian government and corporations to access international capital markets would further undermine long-term growth prospects.

As Western sanctions take their toll on the Russian economy, international financial markets are braced for debt default. On March 8, credit rating agency Fitch downgraded Russian sovereign debt to C, stating that default was imminent. The Russian government was widely expected to miss a $117 million interest payments of two USD bonds on March 16. The bonds were trading at a deep discount -- around 20 cents on the dollar on March 15, indicating a low probability that principal and interest would be paid. The payments were made, taking investors by surprise. Subsequent payments totaling close to $1 billion were also made, demonstrating the willingness of the Russian government to continue servicing its foreign currency debt. Foreign creditors verified that they received the payments, demonstrating that the underlying financial transactions architecture is still operational. For now, at least.

Financial markets are watching closely to see how long this continues. A $2.0 billion (USD) principal payments is due on April 4. This week government offered to buy back some of the bonds, offering rubles in place of USD at the prevailing exchange rate. If the payments are not received in USD by end of a 30-day grace period, credit rating agencies are expected to deem Russian sovereign debt in technical default.

Major sovereign debt default episodes have precipitated financial contagion, often through unexpected channels. The Russian default in 1998 serves as a prime example. In August 1998 Russia restructured its domestic debt and imposed a moratorium on payments on its external debt. A hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), came under heavy financial pressures over the following weeks. This was only partly due to their direct exposures to Russian domestic debt. LTCM's highly leveraged positions in the fixed-income market posed systemic risks to the US financial system and was deemed "too connected to fail" (a precursor to Lehman Brothers in 2009). LTCM was bailed out by a consortium of 14 major financial institutions organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Major sovereign debt defaults have tended to occur in the wake of a domestic financial crisis, the origin of which vary from episode to episode. In the case of the 1998 Russian debt default, the managed exchange rate came under intense pressure. The government raised interest rates to stem capital outflows, driving up the yield on domestic bonds to 50% before the situation was deemed to be unsustainable. Financial crises were not novel at the time. The Asian crisis erupted with the collapse of Thailand's fixed exchange rate regime in July 1997 and quickly spread to Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea and the Philippines. What was unique about the financial crisis in Russia was that the government defaulted on its domestic debt. This was unprecedented at the time and took investors by surprise.

The unique feature of the current situation in Russia is the technical nature of the potential default. Western sanctions could impose restrictions on financial transactions that prevent external creditors from receiving debt service payments.

The Russian government currently has ample fiscal resources

Prior to the invasion on February 24, Russia had an investment grade rating. General government debt was estimated at 20.3 trillion rubles at the end of 2021, an amount close to 16% of GDP projected for the year. This is well below the average for advanced economies (121.6%) and emerging market and developing economies (64.8%)1. Moreover, 3.2 trillion of the debt is in the form of public guarantees, meaning that the government is only required to service the debt in the event that the debtor defaults (largely state-owned enterprises). Government bonds denominated in foreign currency (mostly USD and euro) total around $20 billion (USD). While the local currency value of this debt has varied with the large fluctuations in the ruble since late February, the public debt-to-GDP ratio has remained below 17%.

Russia also has a strong balance of payments position. It has maintained a sizeable current account surplus for several years and is a net creditor from the perspective of international investment. In short, there are no fiscal or external imbalance problems that would prevent Russia from servicing its public or external debt.

Sanctions could result in a "technical default"

Recent debt service payments were processed with the approval of the US Treasury subject to provisions that will expire on May 25. After that, US nationals will no longer be authorized to receive interest, dividend, or maturity payments on debt or equity from Russia’s central bank, national wealth fund and finance ministry.

To further complicate matters, the Russian government issued a decree on March 7 stating that debt service payments to residents of “countries that engage in hostile activities” can only be made in rubles. Six of Russia's 15 Eurobonds have "fallback clauses" which give the government the option of making debt service payment in rubles. Non-residents would then be faced with the problem of exchanging rubles for hard currencies. The decree has yet to be enforced. Last week debt service payments were made in $US on a bond with such a clause. Enforcing the decree on Eurobonds that don't have a fallback clause would certainly constitute a default.

The threat of a Russian debt default has had little impact on financial markets

Against a background of intense geopolitical tensions and heightened uncertainty surrounding the global economic outlook, one might have expected a major sell-off in risky assets. There are few signs of this. The ruble depreciated by 38% against the USD following the invasion on February 24, but has been recovering over the past few weeks (table 1). World oil prices have displayed a similar pattern. Brent briefly peeked at $128 per barrel, before falling back to $111. Equity markets have been calm, surprisingly so. The Cboe VIX index of market volatility declined below levels observed prior to the invasion of Ukraine. Equity prices in Russia have declined by 19% since February 23 while global equity prices registered modest gains (table 1.1).

There is little evidence of a flight to safety. The USD has appreciated by only about 1% in effective terms. The fixed-income market has been dominated by monetary policy developments, showing no signs of a flight to safety. US Treasury yields increased considerably over the past few weeks amid growing concerns about inflationary pressures and strong signals from the Fed that aggressive moves in the fed funds rate may be needed.

Table 1: Changes in Key Indicators Before and After the Invasion

| Date | Crude oil prices | Exchange rates | ||||

| Brent ($US per barrel) | USD effective | Rubles / USD | ||||

| Level | % change | Level | % change | Level | % change | |

| Feb 23 | 96.6 | - | 114.7 | - | 76.8 | - |

| Mar 8 | 128.1 | 32.6 | 117.7 | 2.6 | 105.8 | 37.8 |

| Mar 30 | 111.1 | 15.0 | 116.0 | 1.1 | 84.1 | 9.5 |

Table 1.1: Changes in Key Indicators Before and After the Invasion

| Date | Equity Prices | Bond Prices | ||||||

| S&P Global index | Russia MOEX Index | Dow-Jones Corporate | EMBI Global | |||||

| Level | % change | Level | % change | Level | % change | Level | % change | |

| Feb 23 | 3222.4 | - | 3084.7 | - | 121.3 | - | 918.2 | - |

| Mar 8 | 3178.6 | -1.4 | - | - | 120.0 | -1.1 | 855.0 | -6.9 |

| Mar 30 | 3410.4 | 5.8 | 2513.0 | -18.5 | 119.5 | -1.5 | 884.0 | -3.7 |

Why haven't financial markets responded?

Several factors are at play. One is that the $20 billion in Eurobonds held by non-residents is small compared to previous sovereign debt defaults. In 1998 Russia rescheduled $36 billion in domestic debt, along with $30 billion in Soviet-era debt, which together would amount to $105 billion in current dollar terms (adjusted for inflation using the US CPI). In 2005, Argentina negotiated to reschedule $102.6 billion in foreign currency bonds, equal to $153 billion in current dollar terms. In 2012, Greece rescheduled €206.5 billion marking the largest debt exchange on record. The total amount of sovereign bonds currently in default worldwide is estimated at around $225 billion (as of August 2021).

Another explanation is that foreign investors' holdings of $20 billion in Russia government Eurobonds is small relative to their other exposures. Over 80% of the Russian government's debt (16.5 trillion rubles) was issued domestically in local currency, 18% of which is held by non-residents (2.9 trillion rubles as of end-February). This is equal to $34.5 billion at the current exchange rate (84 rubles / $US at the time of writing). The value of these claims in foreign currency terms has varied with the large fluctuations in the ruble over the past few weeks. In any case, debt service payments on domestic debt are not being sent to non-residents. The main international securities depositories, Euroclear and Clearstream, no longer accept payments in rubles, which effectively prevents foreign investors from accessing their funds.

Restrictions on processing transactions have also created difficulties for the operation of emerging market (EM) fixed-income exchange traded funds (ETFs). The sharp decline in market liquidity, the lack of reliable pricing and restricted access to the domestic bond market make it difficult, if not impossible, for EM ETFs to sell their holdings. Russian bonds were removed from JPMorgan and Bloomberg emerging market (EM) indices on March 31, which will further reduce market liquidity and make pricing all the more difficult. This has minor implications for the asset class as a whole. Russian bonds have a small weight in the major indexes. In December 2021, the weight on Russian bonds in the J.P Morgan Global Diversified Index was only 3.3% and declined to 1.0% at the end of February after Russian bonds were sold off with deep discounts. This gives a good indication of Russia's relative importance in the EM sovereign bond asset class.

Foreign banks have loan exposures to Russian households and businesses totaling $121.5 billion, most of which is concentrated in banks domiciled in Italy, France, and Austria (table 1). Claims by non-residents on Russian corporations also include $15.6 billion in trade credit, $20.1 billion in financial leases and $5.5 billion in other claims (as of December 2021).

Foreign investors have reduced their exposures to Russian debt significantly since 2014

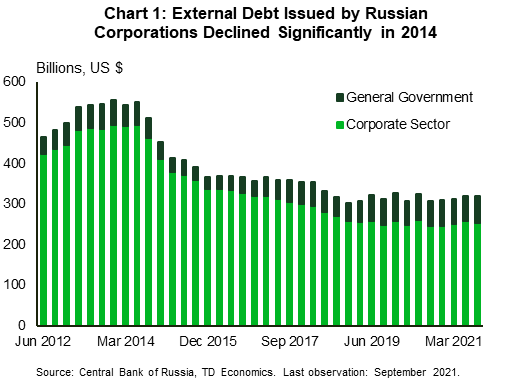

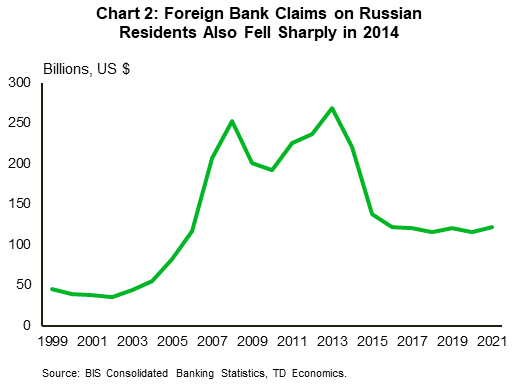

Russian corporations have reduced their reliance external financing significantly since the invasion and annexation of Crimea in early 2014. Claims by non-residents on Russian corporations (including banks) fell by almost one half since December 2013 (chart 1). Foreign banks reduced their loan exposures to Russian households and businesses by one half as well, over the same period (chart 2).

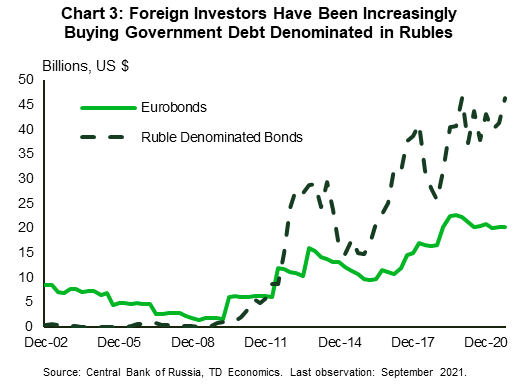

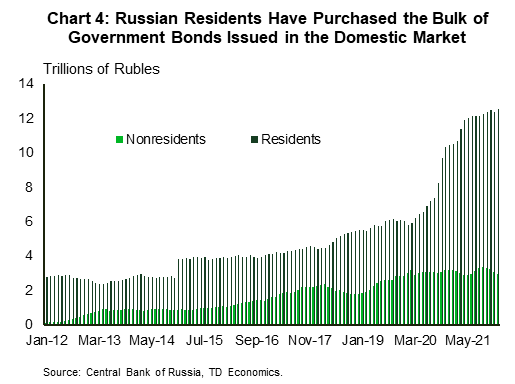

Non-residents increased their holdings of Eurobonds by about $10 billion since 2014, while their holdings of domestic debt increased by around $20 billion (chart 3). Despite this increase, the Russian government has largely relied on domestic residents to meet its financing needs over the past few years (chart 4). It is unlikely that this trend will continue given the dim prospects facing the Russian economy and financial system.

Capital controls have hampered the ability of foreign investors to cut their exposures further. In early March the Russian government introduced capital controls that prevent foreign investors from selling securities and withdrawing funds from the Russian financial system. Russian corporations need to obtain state approval to make debt service payments to creditors from "unfriendly countries".

How would a default on Russian sovereign debt get resolved?

Under a typical sovereign debt default scenario, the government and a creditor committee negotiate a restructuring agreement. This is unlikely to happen until well after geopolitical tensions have subsided. Debtors are eventually compelled to pursue negotiations to regain access to international capital markets. Neither the government nor the corporate sector are in dire need of external financing at the moment. This could change, however, if economic and financial conditions were to deteriorate significantly.

A shortage of foreign currency could constrain the ability of the government and corporations to meet their debt service payments and purchase imports. Western allies have frozen over half of the $643 billion in the CBR's foreign reserve holdings. Restrictions on financial transactions limit foreign currency receipts of Russian corporations. A shortage of foreign currency is already having repercussions. Russian exporters are required to convert 80% of their foreign currency receipts into rubles. The CBR raised the policy interest rate from 9.5% to 20% and introduced capital controls to prevent the conversion from ruble to foreign currency deposits in the banking system.

Even if the Russian government avoids default, they will still not be able to access international capital markets due to the sanctions. If sanctions are removed at some point, a default would tarnish Russia's reputation and be reflected in credit ratings and borrowing costs.

Table 2: Foreign Bank Claims on Russian Residents are Concentrated in a Few Countries

| As of Sept. 2021 | $US billions | Share of total in % |

| Foreign banks | 121.5 | |

| Italy | 25.3 | 20.8 |

| France | 25.2 | 20.7 |

| Austria | 17.5 | 14.4 |

| United States | 14.7 | 12.1 |

| Japan | 9.6 | 7.9 |

| Germany | 8.1 | 6.6 |

| Netherlands | 6.6 | 5.4 |

| Switzerland | 3.7 | 3.1 |

| United Kingdom | 3.0 | 2.5 |

Endnotes

- Based on IMF April 2021 WEO projections.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: